Global Scramble for Africa’s Critical Minerals Drives New Era for Energy and Trade

By Stephen Nkrumah | 11 November 2025

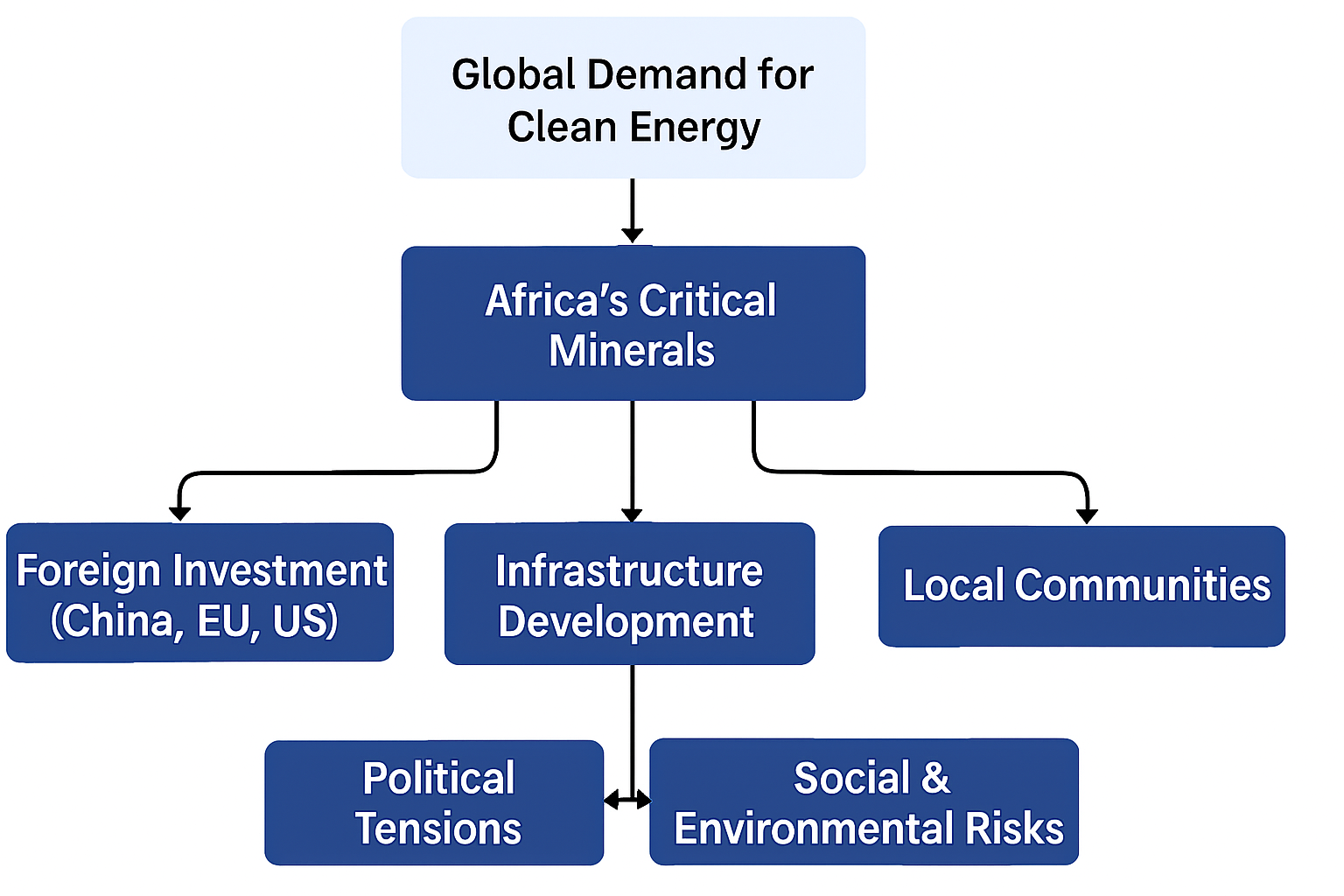

Figure 1: Africa’s Critical Minerals Landscape and Subsequent Risks

Summary

Major world powers are increasing their investments and diplomatic ties across Africa to gain access to essential minerals needed for clean energy, defence, and high-tech industries, making the continent more important on the global stage.

The growing competition among major global powers is changing policies, alliances, and business conditions across Africa. While this creates new economic opportunities, it also puts political pressure on governments to renegotiate contracts, increases regional tensions and security risks, as seen between the DRC and Rwanda, and also heightens economic vulnerability through social unrest, governance issues, and dependence on unstable mineral revenues.

There is a realistic possibility that if the benefits are not shared fairly, it could spark community unrest and labour disputes, as seen in Zambia’s Copperbelt, leading to production delays and supply chain disruptions.

Context

Several African countries, notably the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Zambia, and Namibia, have large reserves of key minerals used in batteries, renewable energy systems, and advanced electronics. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), about 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from the DRC, showing the importance of Africa to global clean energy supply chains.

Recent agreements and investments underscore Africa’s expanding role in international trade and the production of critical minerals. For example, the EU–Namibia partnership on sustainable raw materials and green hydrogen connects resource access with industrial cooperation. Across the continent, many governments are also reviewing tax policies, local content requirements, and environmental standards to maximise value from natural resources. In the DRC, ongoing talks about revising old mining contracts with foreign companies reflect a stronger policy direction focused on transparency and community benefits.

Implications

Politically, the growing struggle for resources is closely linked to national priorities, elections, and coalition dynamics. African governments, in particular, are under constant pressure to convert mineral wealth into tangible public benefits while maintaining the interest of foreign investors. In the DRC, for example, renegotiations and audits have changed expectations about transparency, revenue sharing, and infrastructure-for-minerals exchanges. These efforts can strengthen political legitimacy when clearly communicated and properly managed, as transparent contract reviews and fair revenue distribution help build public trust and investor confidence. However, when policy changes are sudden or poorly coordinated, they can create uncertainty about contract stability, leading to legal disputes, project delays, or even investor withdrawal. For instance, in some mineral-producing countries like Mali, unexpected revisions to tax or ownership terms have resulted in arbitration cases and strained relationships between governments and foreign companies, ultimately undermining the goals of reform.

Regionally, producer nations are working through Africa’s Green Minerals Strategy (AGMS) and other subregional forums to promote value addition and common standards. The African Green Minerals Strategy (AGMS), introduced by the African Union in 2023, serves as a continental framework for integrating critical minerals into green industrialisation plans and strengthening value chains. It focuses on strategically important resources like cobalt, lithium, copper, and rare earth elements, which are essential for batteries, renewable energy systems, and advanced manufacturing. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) holds about 70% of the world’s cobalt reserves, making it a key player in global supply chains for electric vehicles and clean energy technologies. Although still in its early stages, it has begun to gain attention and support from major producers, including the DRC, Zambia, and Namibia. However, progress has been uneven across countries, as differing national priorities and policy approaches continue to limit the overall effectiveness of the continent’s collective bargaining power. At the same time, the ongoing tensions between Rwanda and DRC, partly fueled by competition for control over mineral-rich regions in North and South Kivu, illustrate that access and managing valuable minerals can undermine cooperation, trust, and shared governance of Africa’s mineral resources, making it harder to achieve sustainable and peaceful development.

Operationally, the increasing flow of investment is accelerating the development of infrastructure, including power plants, roads, rail lines, and ports, such as the rehabilitation of the TAZARA railway linking Zambia and Tanzania, hydropower upgrades in the DRC’s Inga region, and port expansion projects in Namibia’s Walvis Bay and South Africa’s Durban, which aim to support mineral transport and export efficiency. However, it also exposes companies to changing regulations, licensing delays, and stricter local content requirements. The African Minerals Development Centre (AMDC) emphasises that clear and consistent rules on value addition and employment can improve operational efficiency and investor confidence.

Recent protests in Zambia’s Copperbelt were driven by concerns about unfair labour practices, low compensation for displaced communities, and environmental pollution linked to mining operations. In some cases, the demonstrations turned violent and disrupted production. These events demonstrate how unresolved social and environmental issues can rapidly escalate into significant risks for both mining companies and local stability. Companies that neglect community engagement often face longer disruptions and higher security costs. Transport routes linking mines to ports remain major bottlenecks, where congestion, bad weather, and customs delays can worsen schedule risks and increase demurrage expenses.

Security risks are highest in areas with weak governance and where illegal economic activities overlap with mining operations. Growing foreign interest can fuel competition among local power brokers, increasing the chances of corruption, illegal artisanal mining, and mineral smuggling. Private military groups such as the Wagner Group have been involved in protecting or exploiting resource sites in countries like Mali, the Central African Republic, and Sudan, creating serious concerns about governance and accountability. In Mali, for instance, Human Rights Watch, 2024 reported that Malian armed forces and Wagner Group operatives unlawfully killed and summarily executed several dozen civilians since December 2023 during joint counterinsurgency operations, including in areas near gold-mining zones. The report further noted that at least 14 civilians, including 4 children, were killed in military drone strikes on a wedding and a burial in February 2024. These abuses underscore how foreign-linked security operations around mineral areas can destabilise communities and disrupt legitimate trade activities.

Economically, rising mineral exports bring higher revenues and more foreign exchange, but depending too heavily on a few commodities makes national budgets vulnerable to price swings and Dutch disease effects, which occur when a resource boom strengthens a country’s currency, making its other sectors, like manufacturing and agriculture, less competitive and harder to sustain. Without strong policies for savings and stabilisation, sudden windfalls can worsen boom-and-bust cycles. The Africa’s Green Minerals Strategy (AGMS) promotes local content, good environmental and social governance, and local processing to increase value retention. However, forcing these measures too early without reliable energy, skilled labour, and financing can discourage investment or push firms elsewhere. Where power and infrastructure improve and legal systems strengthen, gradual processing like cathode precursor production near low-carbon energy sources can become feasible.

USGS/Unsplash

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

It is highly likely that the DRC will announce updates on legacy contract audits and revenue-sharing plans, with closer checks on cobalt and copper joint ventures, and limited disclosures may lead to public calls for more transparency.

It is likely that labour tensions, like in Zambia’s Copperbelt, will rise again over shift patterns and environmental concerns, possibly causing short work stoppages at some sites unless engagement plans are improved.

It is likely that ministries in Namibia will release temporary guidelines on local content and Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) reporting under the EU–Namibia sustainable raw materials and green hydrogen partnership, which will increase short-term compliance requirements for explorers.

It is likely that the African Minerals Development Centre (AMDC) will publish clarifications on beneficiation priorities and skills localisation targets under Africa’s Green Minerals Strategy (AGMS), signalling what investors can expect.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

It is highly likely that the EU–Namibia partnership will lead to concrete Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) for pilot processing projects, such as precursor materials and grid-support upgrades, which could make policies more complicated and increase the need for careful checks.

It is a realistic possibility that at least one producer will introduce royalty or tax adjustments, or create or expand mineral revenue stabilisation funds, to help manage price volatility and foreign exchange pressures.

It is likely that plans to rehabilitate and expand the TAZARA and northern corridors will be proposed with co-investment offers from major powers, linking mineral access to rail logistics, though public–private structuring may pose key execution risks.

Long-term (>1 year)

It is likely that uneven benefit sharing and ongoing resettlement or environmental grievances will intensify around major assets in the DRC and Zambia’s Copperbelt, raising the risk of periodic disruptions unless revenue transparency, local procurement, and service delivery clearly improve.

It is highly likely that multi-country value chains will form around key energy hubs, with DRC and Zambia developing hydro-powered zones for precursor materials, and Namibia focusing on renewables-based zones for refining steps and green hydrogen-related inputs.

It is likely that broader contract disclosure, independent audits, and AGMS-aligned ESG reporting will become standard for accessing concessional finance and premium offtake deals, while operators that do not comply may face higher risks of losing their position.