Nile River Politics and Climate Change

By Trishnakhi Parashar | 2 December 2025

Summary

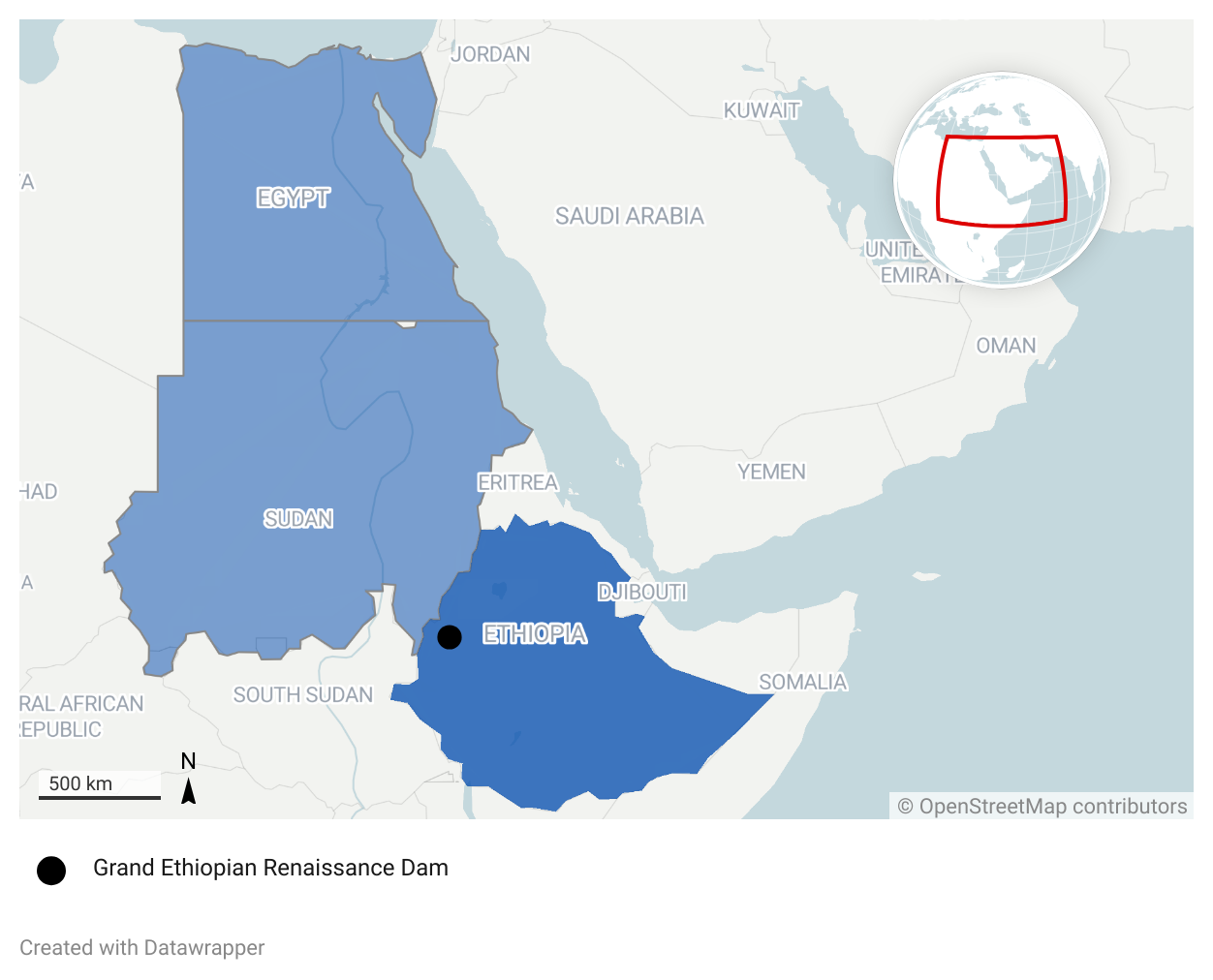

The dispute over the operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has reached a political deadlock, with Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia still trying to reach a consensus on water-sharing and dam management.

Egypt faces rising water insecurity due to climate change and upstream projects on the Nile River, while Ethiopia is working to generate hydroelectric power to meet its energy needs.

The projected increase in water-flow variability will make the current diplomatic deadlock unsustainable, pointing out the necessity for greater regional cooperation to avoid potential humanitarian crises.

Context

Ethiopia has recently inaugurated the largest hydroelectric dam in Africa, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile, adding renewed pressure to regional political dynamics over the shared river. The dam cost Ethiopia nearly USD 4.8-5b and is situated close to the Sudan–Ethiopia border. In February 2022, the dam began generating electricity for the first time. Once all its turbines are operational, it is expected to produce up to 6,000 megawatts of electricity.

The dam’s expansion comes at a time when climate change is intensifying water stress across the Nile Basin. Rising temperatures, combined with shifting rainfall patterns and more frequent droughts, are affecting overall river flows. In particular, Egypt is experiencing a dual crisis centred on the Nile River. The Nile is the source of approximately 97% of its fresh water for Egypt.

The geopolitical tension has existed from the time of construction and continues now that the dam became operational on 9 September 2025. The primary cause of tension is the failure to conclude a legally binding agreement between the upstream state of Ethiopia and the downstream states, Egypt and Sudan. The discussions also center on the dam’s filling and annual operation.

Egypt insists on legal guarantees to protect its historic water share. It considers any significant reduction in the river’s flow as an existential threat to its civilisation. Sudan faces a peculiar situation. Apart from the concerns about the dam, it would be directly affected by the consequences of any escalation between its neighbours. Sudan seeks assurances that the GERD operations will not compromise the safety of its own dams, electricity generation, or agricultural stability. On the contrary, Ethiopia perceives the GERD as a crucial project for self-sufficiency, which is essential for its power production and national development. It also has plans to increase electricity exports to neighbouring countries to expand into the Middle East.

Driven by different national interests, despite multiple rounds of trilateral negotiations and several external mediation attempts, none of these negotiations has been able to formulate a mutually accepted agreement.

Implications

The inauguration of the GERD intensified existing tensions among Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia, as negotiations continued without a binding agreement. This hydro-political tension is further compounded by the already deteriorating challenges of climate change vis-à-vis regional water stability. The AU and other mediators are continuing to facilitate talks, but the political deadlock raises the risk of diplomatic friction. Climate change is making the Nile’s flow unpredictable, putting more political pressure on the downstream state of Egypt to pursue broader international engagement to secure its water.

Uncertainty over the dam’s operations poses serious risks to Sudan and Egypt’s water management. Egypt also argues that uncoordinated upstream water releases could threaten its water security, particularly in times of severe drought. Fluctuating water flows could hinder irrigation networks and increase the burden on water-saving and desalination projects. Sudan is also concerned about the timing of water releases, which might affect the safety and efficiency of its own dams.

The consequences of being unable to conclude a legally binding framework for the GERD operations heighten not only operational uncertainties but also the potential for regional instability. Any unintended miscommunication or sudden changes in operation could elevate tensions along the Sudan–Ethiopia border, where past disputes have already strained relations. Even though the likelihood of direct conflict remains very low, sustained political mistrust and unresolved water sharing may contribute to broader security unpredictability among the states.

Continued uncoordinated water management may affect agricultural production across Sudan and Egypt, raising costs and increasing dependence on food imports. Egypt’s long-term development projects, particularly related to irrigation, may encounter postponements or higher expenditure due to the need for extensive water management. Simultaneously, Ethiopia expects substantial economic profit from exporting electricity, although unpredictable regional dynamics could limit the revenue potential.

Ethiopia Office/Wikimedia

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan will likely maintain diplomatic engagement through the AU, but negotiations are unlikely to provide a binding framework on dam operations in the short term.

Technical committees are likely to review and resume data-sharing discussions, though progress will be limited by political mistrust and other natural reasons.

There is a realistic possibility that other mediators may step in, but in the short term, they are unlikely to succeed in bringing the parties to the negotiating table.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

Fluctuations in rainfall and rising temperatures are likely to intensify downstream water stress, increasing diplomatic pressure on Ethiopia to cooperate.

Egypt is likely to invest more in desalination and irrigation-efficiency projects to mitigate dependency, though financial limitations could slow the process.

A realistic possibility is that Egypt might face domestic instability to some extent, due to rising concerns over water security compounded by rapid population growth.

Long-term (>1 year)

Without a legally binding water-management agreement, prolonged climate challenges could be highly likely to decline in agricultural productivity with broader economic repercussions in the downstream states.

Slow progress in regional cooperation, tensions surrounding the GERD are likely to contribute to broader instability in contested border areas; however, the likelihood of direct conflict remains low.

Additional mediators are highly likely to pursue renewed negotiation, to break the current deadlock revolving around the GERD, potentially increasing pressure on Ethiopia to engage; however, the prospect of reaching an agreement remains a realistic possibility rather than a certainty.