Pits for AI? Repurposing Plutonium for Next-Generation Data Centers

By Larissa Alves Lozano | 3 December 2025

Summary

The global boom of data centers and their need for small modular reactors has exposed a drastic nuclear fuel shortage, and unused plutonium could be an alternative.

Besides potentially powering data centers, reducing the volume of high-level nuclear waste, and creating a legitimate non-military use of plutonium, MOX production and reprocessing pose proliferation concerns and face technical and financial obstacles.

If nuclear fuel sources are not diversified beyond HALEU, Europe and the United States risk falling behind in the global AI data center race due to a lack of power.

Plutonium: An Underutilised Nuclear Power Source

Ever since the data center industry boomed in 2023 with the dramatic increase of AI platforms, nuclear energy, specifically Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), has been sought by major tech companies to provide on-site power for their data centers, supporting cloud storage and AI operations.

Most SMRss are being designed to use High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU), a uranium-based fuel with enrichment levels up to 20%. Due to their small form factor, SMRs require high power density and less frequent refuelling in comparison to conventional large nuclear reactors, which utilise 3 - 5 % low-enriched uranium (LEU) fuel.

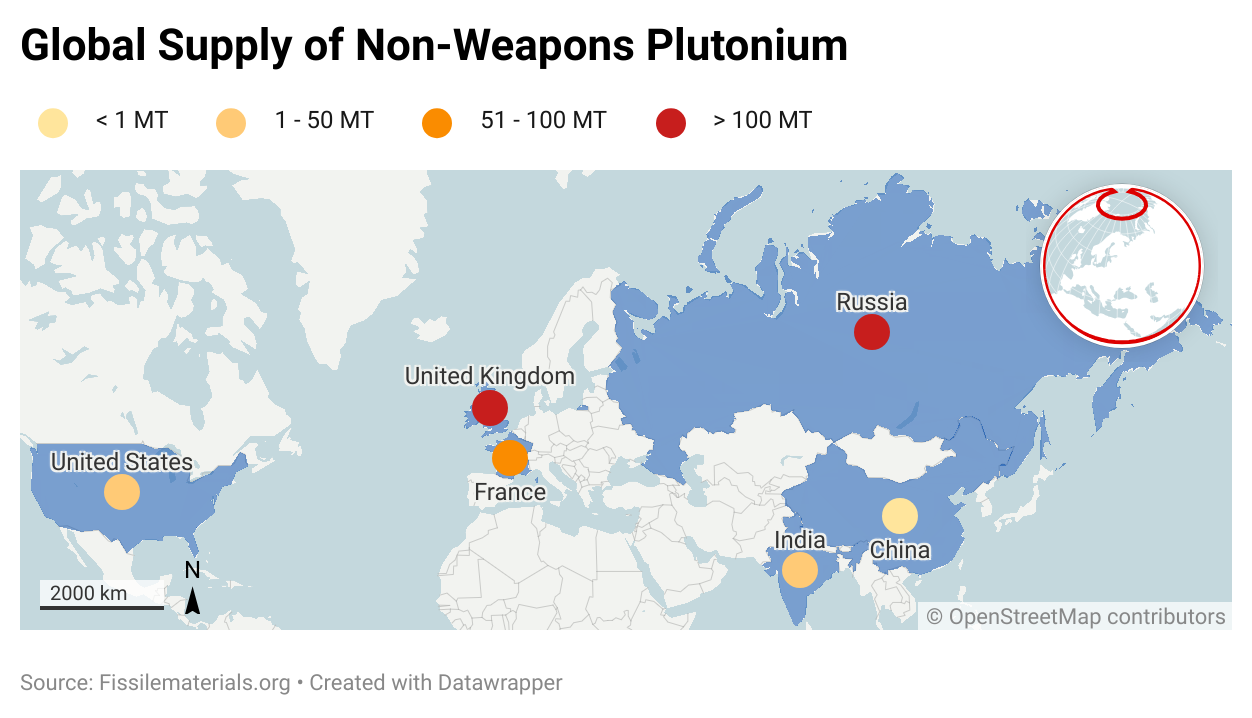

The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that HALEU annual demand could reach about 50 metric tons (MT) per year by 2035, with predictions being higher when considering SMR-powered data center projects in Europe and the Middle East. Russian company TENEX is the only commercial producer and supplier of HALEU in the world, and HALEU investments in the United States, China, and the United Kingdom are nowhere close to matching commercial demand predictions. As the data center industry has invested over USD 500b in SMRs, the race for nuclear fuel will only accelerate, and despite being one of the rarest elements on the periodic table, plutonium could be an answer.

As of 2024, the global stockpile of separated plutonium was about 565 MT, resulting from nuclear reactor waste products and nuclear warhead pit production. Of this total amount, 425 MT is deemed “excess” to nuclear weapons production and is being downblended and stored. With a decline of MOX fuel production and reprocessing, about 90% of potential energy sits unused in spent fuel or diluted plutonium barrels. There is a drastic need for non-military uses of plutonium, and SMRs for AI and data centers could be an option.

Plutonium Fuel: Old Challenges and New Opportunities

The largest challenge with plutonium production is its direct link to nuclear weapons, more so than uranium, but it is possible to use plutonium for nuclear power as Mixed-Oxide Fuel (MOX), which is produced either by mixing depleted uranium dioxide and plutonium dioxide into ceramic pellets. Plutonium dioxide is obtained either by diluting weapons-grade plutonium or reprocessing spent fuel. France, the Netherlands, and Japan all use MOX fuel in some of their nuclear reactors, thus showing a potential for non-military plutonium uses. However, only France and Russia currently operate commercial-scale reprocessing facilities, while both the US and UK ceased reprocessing in 1977 and 2022, respectively.

One of the largest challenges in utilising plutonium as nuclear fuel is the financial cost of reprocessing and Mixed Oxide Fuel (MOX) production. In the United States, the current “dilute and dispose” process to render “excess” weapons-grade plutonium unusable costs over USD 18b for a mere 34 MT of plutonium over 31 years. In comparison, MOX fuel production costs USD 17b in the US, but Orano has managed to operate France’s La Hague at a lower cost of approximately Euros 1.6b invested over 8 years. Even if countries remain opposed to reprocessing, there remains enough weapons-grade plutonium that can be diluted with uranium dioxide to produce MOX fuel, and stored non-weapons plutonium can also be retrieved for that purpose. While HALEU production is estimated to cost the US USD 3m per kilogram, MOX would be a better investment, with estimates ranging from USD $300 to $1600 per kilogram, with the average cost of reprocessing being USD $605 per kilogram between 2025 and 2085. Despite the high price, MOX fuel production would be more advantageous in the long run in relation to the current disposal process that wastes the potential of the existing plutonium supply.

If multilateral support for plutonium-based fuels is fostered, such as Japan sending its spent fuel to be recycled in France, the financial and infrastructure burden can be minimised to ensure the potential energy in spent fuel and excess weapons-grade plutonium is not wasted. It is imperative to make the most of every nuclear fuel source available to fulfil power-intensive SMR and AI developments.

The global scalability of SMRs to power data centers for AI developments will be determined by nuclear fuel availability. Thus, the world must look beyond HALEU, overcome the financial fear of MOX fuel production, and channel the neglected potential of excess plutonium.

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

HALEU fuel production is highly unlikely to meet the projected demand for SMRs.

In order for countries to consider MOX fuel for SMRs, it is imperative to have legislation against cost overruns. Thus, it is highly likely that multilateral MOX fuel production efforts will be considered to minimise production costs and scale production.

Long-term (>1 year)

It is unlikely that political and public opposition surrounding spent fuel reprocessing and MOX fuel production will quickly go away, but strides have been made through recent Trump executive orders and France’s La Hague expansion plans for spent fuel storage and MOX production.

With a shortage of HALEU fuel, there is a realistic probability that small modular reactor companies should follow NuScale’s MOX-compatible SMR design to promote a peaceful purpose for the global excess plutonium supply.

Plutonium fuel investments are highly likely to aid the multilateral push to decouple from the Russian monopoly on uranium-based nuclear fuels to power SMRs for AI data centers.