From Wales to The Hague: NATO Members Agree to Spend 5% of GDP on Defence

Milica Starinac | 7 July 2025

Summary

NATO allies have agreed to a new defence spending pledge of 5% of GDP, driven by ongoing threats from Russia, growing US pressure and Europe’s broader rearmament efforts.

While the pledge signals a major shift in NATO’s defence posture, it risks deepening internal divides due to uneven economic capacities, threat perceptions, and potential strain on social spending in fiscally constrained member states.

Member states will acknowledge the pledge and begin implementation in the short term, but long-term fulfilment will be uneven, with likely domestic backlash in some countries and rising East-West friction within the alliance.

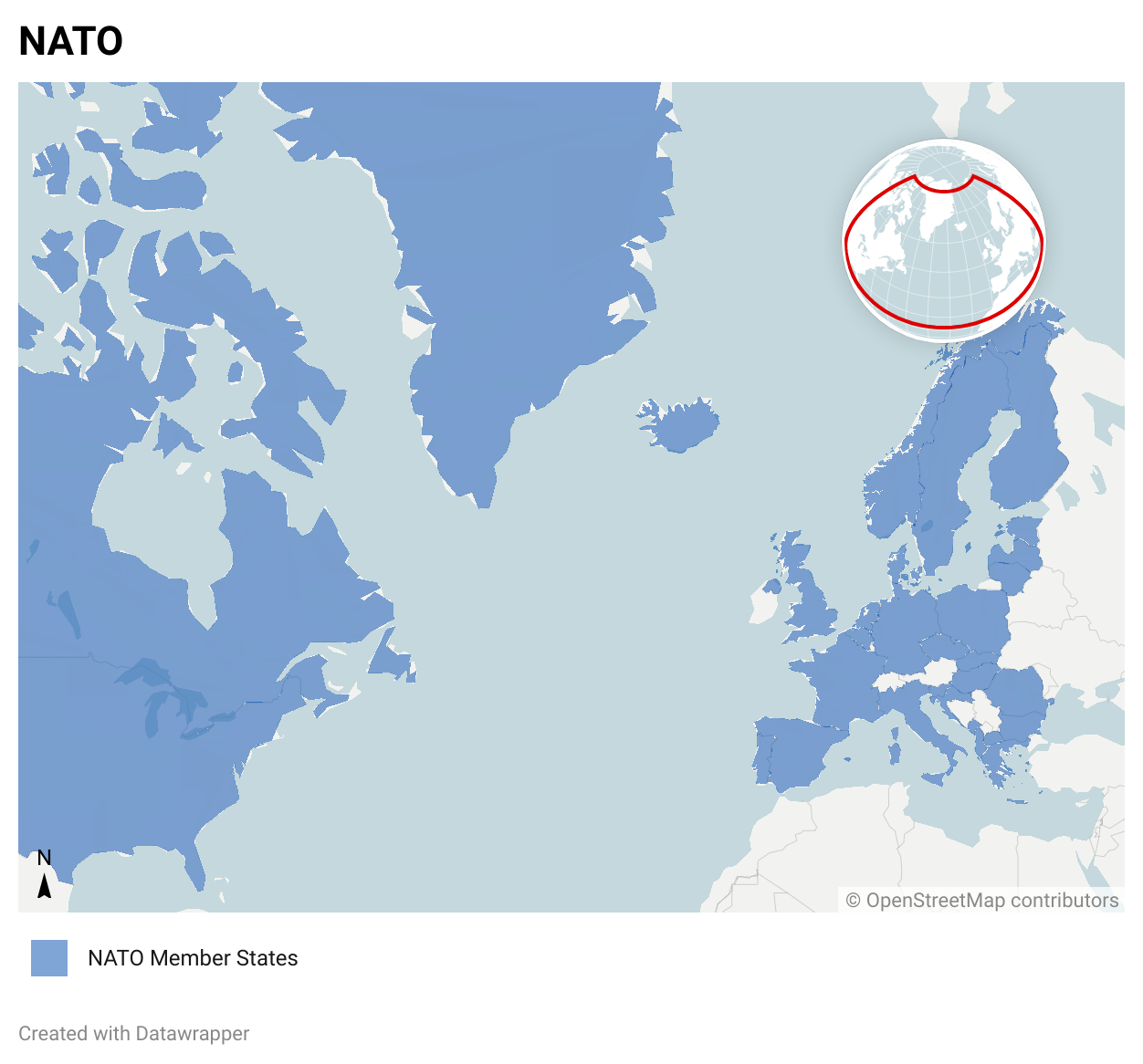

NATO member states have agreed to dramatically ramp up their defence spending pledge to 5% of GDP. The news came ahead of and was confirmed at the NATO summit in the Hague, held on 24 and 25 June. Secretary General Mark Rutte proposed the ambitious plan earlier in June, at the meeting of defence ministers in Brussels, but the 5% figure has been brought up long before — by the United States (US) President Donald Trump, two weeks before his inauguration in January. Trump is no longer able to unilaterally withdraw the US from NATO without Congress approval, as he threatened during his first term, since Congress passed legislation in 2023 barring any president from such unilateral actions. However, European NATO allies are keen on satisfying Trump’s demands for greater spending, as he still has considerable power in areas such as troop allocation, and considering he previously threatened not aiding allies which “don’t pay” in case Russia attacks them.

Trump’s insistence is not the sole factor behind this increase — Europe has been steadily increasing defence spending since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and particularly after the 2022 Russian invasion — in 2024, the European defence spending grew by 11.7% in real terms, reaching USD 457b. Moreover, the EU is stepping up as a defence actor with the ambitious ReArm Europe plan, aiming to secure about EUR 800b for defence spending in the next 5 years.

The defence spending threshold has long been a point of contention in the transatlantic security partnership, but no other US president put as much weight on it as Trump. At the 2014 Wales summit, NATO allies committed to increase their defence spending to 2% of GDP — a goal achieved by 23 out of 32 member states by the 2024 estimates. Countries falling behind the threshold 11 years after it was agreed upon include Canada, Italy and Belgium, as well as Spain, which secured an opt-out from the new increase plan while reaffirming commitment to NATO and to reaching the 2.1% with the upcoming budget. Another country which will apparently not follow the 5% guideline is the US, as Trump voiced his opposition to applying the rule to the US, which currently spends 3.4% of GDP on defence and remains by far the highest spender in this field globally, with USD 997b defence expenditure in 2024.

Judging by where NATO allies stand at the moment, despite significant defence expenditure increases in the past decade, the new pledge will not make an easy target. This is why Rutte proposed a formula that entails 3.5% of GDP allocated to “hard defence” expenditure, such as military equipment and personnel, while the 1.5% of GDP will be counted as expenditure related to military mobility, cybersecurity and other dual-use investments. Still, the 3.5% threshold is no small feat either — the only NATO member currently surpassing it is Poland with 4.12% of GDP allocated for defence. The Baltic states are not far behind and have been pushing for setting a shorter timeframe for achieving the new spending goal across the alliance, while Rutte’s initial plan envisaged 2032 as the target year. At the summit, the deadline was pushed until 2035.

The 5% target risks exacerbating internal NATO rifts, as eastern members seek robust deterrence against Russia, while southern allies—facing lower perceived threats and tighter fiscal space—are reluctant or unable to scale up spending at the same pace. High levels of debt and social spending are the biggest impediments for many European states, and employing “guns or butter” economics is likely to fuel grievances in their electorates. Germany and Sweden have rewritten their debt rules in order to pay for the defence spending surge, while Greece, which is among top spenders in NATO judging by the GDP percentage, provides an example of how dramatic increases in defence spending could negatively affect the social safety net and living standards of citizens. The 5% pledge marks a major shift in NATO’s defence posture, but uneven threat perceptions and economic constraints risk widening internal divides. Without fair burden-sharing, the push for unity could strain the alliance instead.

NATO

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

It is likely that the majority of defence budget proposals for 2026 increase at a higher rate than in the previous year, signalling a resolve of member states to improve their defence posture.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

NATO Member states are likely to start increasing defence procurement, also aligned with ReArm Europe plan. Joint procurements are also materialised and increased.

Long-term (>1 year)

It is likely that certain NATO members, including but not limited to Spain, Portugal or Italy, will face domestic backlash in the next 1-2 years should they drastically ramp up defence spending at the expense of social and welfare programmes. On the other hand, it is possible that a rift between Eastern and Western European members might deepen if the latter do not show a significant resolve to fulfil the commitment, while the former continue to feel threatened by Russia amid the prolonged war in Ukraine.

Poland, the Baltic States, and likely Germany and the UK will be among the countries to fulfil the 5% pledge by 2032, however it is unlikely that all member states will do so in that timeframe.