From ‘New Kazakhstan’ to a New Constitution: Tokayev’s Next Push

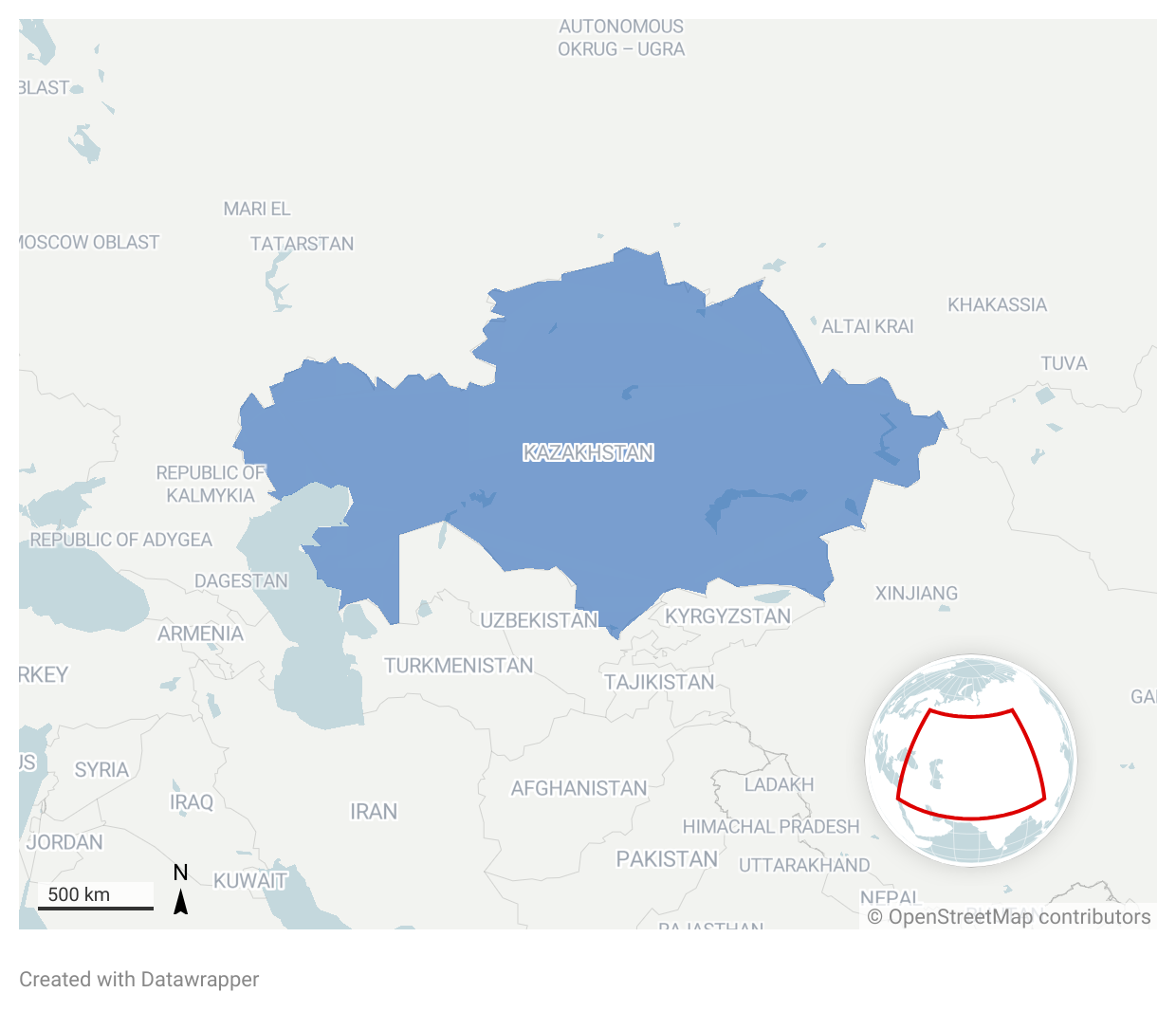

By Erlan Benedis-Grab | 26 January 2026

Summary

In January 2026, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev used his address to the National Kurultai to expand on reforms first outlined in his 8 September 2025 state of the nation address, proposing to abolish the Senate and the state counsellor post, create a vice presidency, and shift Kazakhstan to a unicameral parliament.

President Tokayev’s recent messaging, paired with the creation of a Constitutional Commission—signals intent to pursue a sweeping constitutional rewrite, even if a new constitution has not been formally announced.

Tokayev has proposed electing a future unicameral parliament exclusively via party lists, reversing the mixed system (party lists/single-mandate districts) introduced after the 2022 unrest.

Taken together, these reforms are likely to further centralise political authority around the presidency rather than disperse it, despite President Tokayev’s presentation of them as part of a broader consensus-reform agenda.

Context

Following the deadly unrest in January 2022, President Tokayev promised a new wave of reforms, titled “New Kazakhstan”, promising a shift toward stronger institutions and reduced presidential dominance. Several years on, whilst Tokayev has curbed former President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s old guard, Kazakhstan’s tightly managed political system has remained essentially unchanged. This situation may change in the coming year.

On 8 September 2025, in his state of the nation address, Tokayev proposed major changes to Kazakhstan’s constitution, including abolishing the Senate of Kazakhstan. To advance this agenda, he appointed State Councilor Erlan Qarin to lead the presidential working group on parliamentary reform. Additionally, the 30-member group includes prominent lawyers, legislators, political scientists, and experts. In January 2026, he escalated the process by establishing a Commission on Constitutional Reform, chaired by Constitutional Court head Elvira Azimova, with Karin serving as a deputy chair, tasked with consolidating proposals and drafting constitutional amendments ahead of a planned referendum to approve these changes in 2027. While Tokayev has rolled out the initiative gradually and emphasised consultation, the reform process remains tightly managed from Ak Orda.

Tokayev proposed merging the National Kurultai and the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan into a single Khalyk Kenesi (People’s Council). The new body would consolidate the roles previously split between the two institutions, serving as a platform for public consultation, interethnic cohesion, and building broad-based citizen–state consensus.

Some Majlis deputies are currently elected in single-member districts, but the proposed reforms would return Kazakhstan to a fully proportional, party-list system—reversing Tokayev’s post-January 2022 changes. Since 2007, the Majlis was elected by party lists; after the 2022 unrest, Tokayev reinstated a mixed model (70% party lists, 30% single-member seats). These reforms were framed as technocratic modernisation, while also consolidating Tokayev’s legitimacy by further sidelining residual Nazarbayev-era influence.

Lastly, Tokayev proposed abolishing the State Councilor post and creating a Vice Presidency. The Vice Presidency, which was abolished in 1996 would represent Kazakhstan abroad, and the head of state in parliament. The proposed Vice Presidency is described in broad terms, but its precise portfolio and legal authority remain to be specified in the future.

Implications

Kazakhstan is framing these reforms as both an efficiency drive and a dispersion of authority. The proposed Vice Presidency is presented as distributing executive functions, while the People’s Council is positioned to take on expanded oversight power on formal institutions. The deeper question, however, is whether formal checks can meaningfully constrain power in the absence of a culture of political competition and balancing.

In Kazakhstan, a non-competitive authoritarian state, the party system is tightly controlled. Parliament is composed entirely of pro-government parties or controlled opposition. In this context, a unicameral legislature is likely to be even more manageable for the executive. At the same time, the Senate has long been criticised as a largely symbolic institution, akin to a political retirement home.

Similarly, eliminating single-member constituencies is presented as a step forward, but in Kazakhstan’s context, it tightens executive control over candidate selection. Candidates without the explicit support of the ruling Amanat (Nur Otan) party will highly likely be excluded from the new parliament.

The timing of these reforms intersects with the question of presidential succession. Tokayev is expected to conclude his term in 2029, creating uncertainty around Kazakhstan’s next political transition. Under current rules, the Speaker of the Senate is first in the line of succession. Introducing a Vice Presidency would create another powerful institutional post—one that could offer Tokayev an avenue to retain influence after leaving office, echoing post-Soviet precedents such as Nazarbayev’s enhanced role via the Security Council. However, a vice presidency would be designed to reduce ambiguity in a transition by establishing a clearer chain of command and a more predictable order of succession in a crisis.

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

It is highly likely Amanat and other loyal parties (Aq Jol, Respublica, Auyl) will issue statements supporting the constitutional reforms. This will present the perception of broad political consensus and minimise resistance.

It is almost certain Government media will amplify messages that the bicameral system is outdated. Commentaries will stress international comparisons and emphasise streamlined governance to prepare public opinion for the reforms.

It is likely Limited parliamentary or civil-society contestation, with debate largely contained within approved expert and media channels.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

It is almost certain that the Constitutional Commission will move from concept papers to draft amendment language and a consolidated “single package” narrative.

Long-term (>1 year)

It is likely Kazakhstan will likely hold the referendum in 2027 and almost certainly before 2029. It is almost certain, given Kazakhstan's controlled political environment and past referendum outcomes, that the result will be an overwhelming “Yes”.