Uzbekistan’s Critical Minerals Diplomacy: Deepening Cooperation with the United States

By Erlan Benedis-Grab | 18 February 2026

Summary

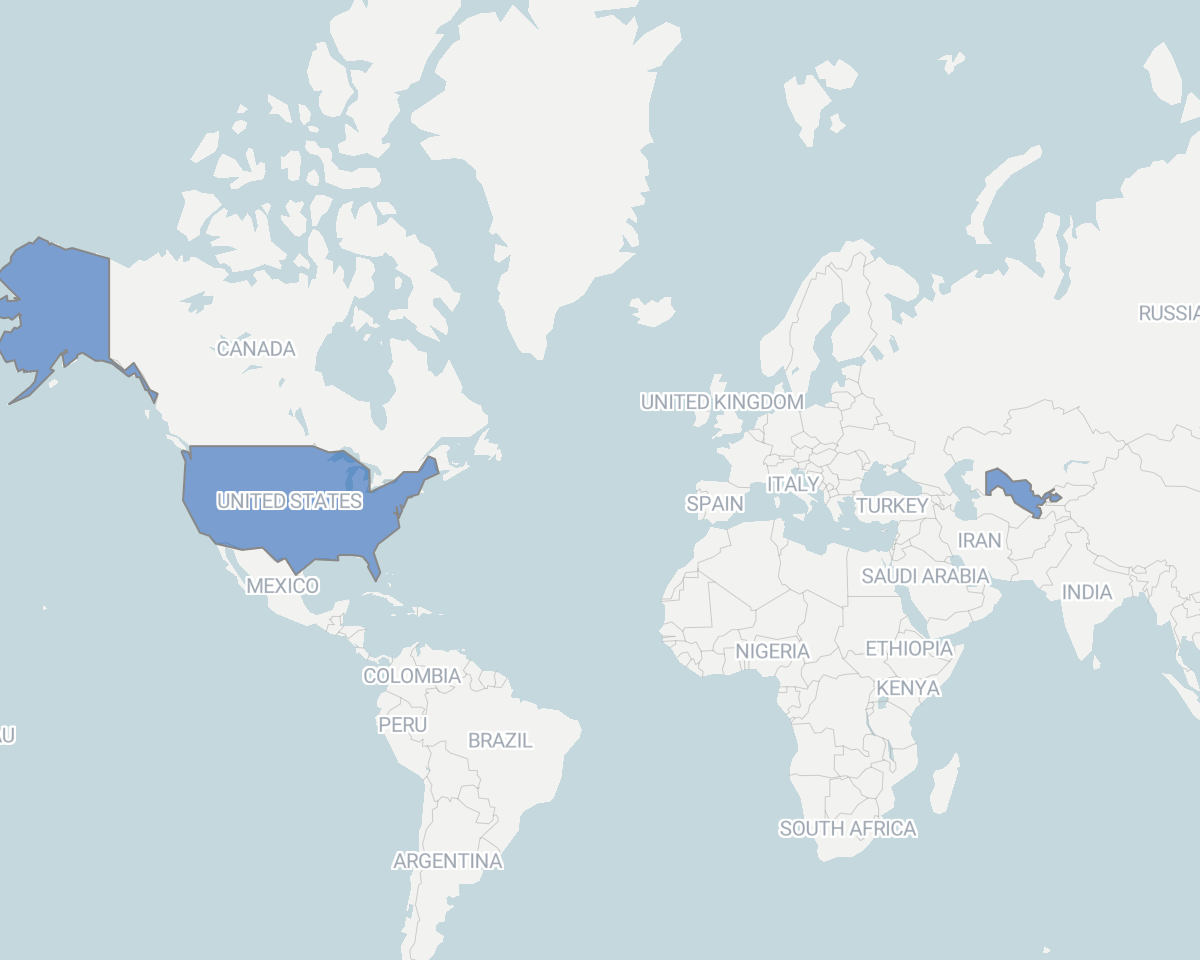

On 4 February 2026, Uzbekistan and the U.S. signed a new Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to build on a previous MoU from 2024 regarding critical minerals. This was signed alongside a Washington ministerial that brought together Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and dozens of other countries.

The deal integrates Uzbekistan into Washington’s broader critical minerals push, as demonstrated by the recent launch of FORGE & Project Vault.

Uzbekistan stands to gain if the MoU translates into bankable projects and committed financing. At the same time, Tashkent will need to employ careful messaging, emphasising the arrangement’s non-exclusive, commercial character to blunt Chinese backlash without deterring Western investors.

Context

On 4 February 2026, Uzbekistan and the United States signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on Securing Supply in the Mining and Processing of Critical Minerals and Rare Earths.

It builds on a previous MoU to strengthen cooperation between the United States and Uzbekistan on critical minerals, signed on 16 September 2024 under the Biden administration.

This step coincided with Foreign Minister Bakhtiyor Saidov’s trip to Washington, D.C., where he attended the inaugural Critical Minerals Ministerial hosted by U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio. Kazakhstan’s Foreign Minister, Yermek Kocherbáiev, was also in attendance, in addition to 43 other countries.

Underscoring these events was the United States’s launch of FORGE (the Forum on Resource, Geostrategic Engagement) & Project Vault. FORGE aims to reduce reliance on China-dominated critical-mineral supply chains, potentially through a price floor and a new partner “zone” to steer production and investment, though key details remain unclear. Project Vault, also announced in February 2026, is a $12bn U.S.-backed stockpile of critical minerals like copper and lithium to cushion supply disruptions. In that context, Uzbekistan’s agreement fits a wider web of U.S. action plans and MoUs aimed at diversifying the supply of critical minerals away from China.

Implications

A key theme of President Trump’s second term is American self-reliance—especially in industries where China controls a decisive share of the supply chain. Uzbekistan, which hosts dozens of critical mineral deposits (tungsten, lithium, vanadium, titanium, germanium, and graphite), has much to gain from potentially becoming a preferential partner in these new critical mineral frameworks.

This MoU builds on the U.S.–Uzbekistan critical minerals cooperation launched in 2024 memorandum signed under the Biden administration, and formalises that cooperation at a higher political level, with a government-to-government MoU signed in February 2026 by Uzbekistan’s foreign minister. It can be read as fitting into the broader pattern of Uzbekistan hedging toward the West.

The practical next step will be for the United States to translate this MoU into concrete investment in Uzbekistan. Washington should identify a small set of priority projects, mobilise public and private capital, and ensure they meet transparency and ESG standards—most likely by leveraging U.S. financing tools such as EXIM and the DFC. Getting U.S.-led projects off the ground would show this isn’t just a statement of intent, but rather a policy that can actually be implemented.

Uzbekistan follows a multi-vector foreign policy, seeking to balance relationships with Russia, China and the United States. This move will be sure to anger China, which has already warned against “undermining the international economic and trade order through rules imposed by small groups.”

Separately, Russia’s neo-Soviet attitude to Uzbekistan, will ensure that Russia treats deeper U.S.–Uzbek cooperation as a sphere-of-influence issue, and Russia still has tools, from migration, remittances and information pressure, to raise the costs of any perceived drift. Similar to J.D. Vance’s historic visit to Armenia/Azerbaijan, the United States is showing that diplomacy and investment can gain traction in regions considered to be in Russia’s backyard.

Thus, Tashkent will likely frame the deal as a non-exclusive, commercially / investment driven partnership rather than a political alignment, while continuing to welcome Chinese and Russian trade and investment.

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

It is likely that the United States will formalise the list of countries invited into the FORGE organisation and the specific rules and bylaws of this organisation.

It is likely that the MoU will translate into a working-level project list (priority minerals, potential sites etc..)

Medium-term (3 - 12 months)

There is a realistic possibility that China responds to U.S. pressure through commercial competition and diplomatic signalling; it is unlikely to pursue overt punishment against Uzbekistan in the near term.

It is likely that investment linked to Project Vault (backed by EXIM and private capital) begins to shape the market by financing non-China supply of critical minerals.

However, there is a realistic possibility that FORGE falls short of its full vision: even if it is institutionally established, it may ultimately become a loose coordination forum among countries unwilling to commit to enforceable pricing rules.

Long-term (>1 year)

There is a realistic possibility that investor confidence hinges increasingly on Uzbekistan’s regulatory credibility (stable licensing, predictable tax code and dispute resolution), which could become a differentiator in attracting long-term Western capital.

There is a realistic possibility that Astana and Tashkent move toward regional cooperation on critical minerals, including signing formal agreements and cooperation protocols.