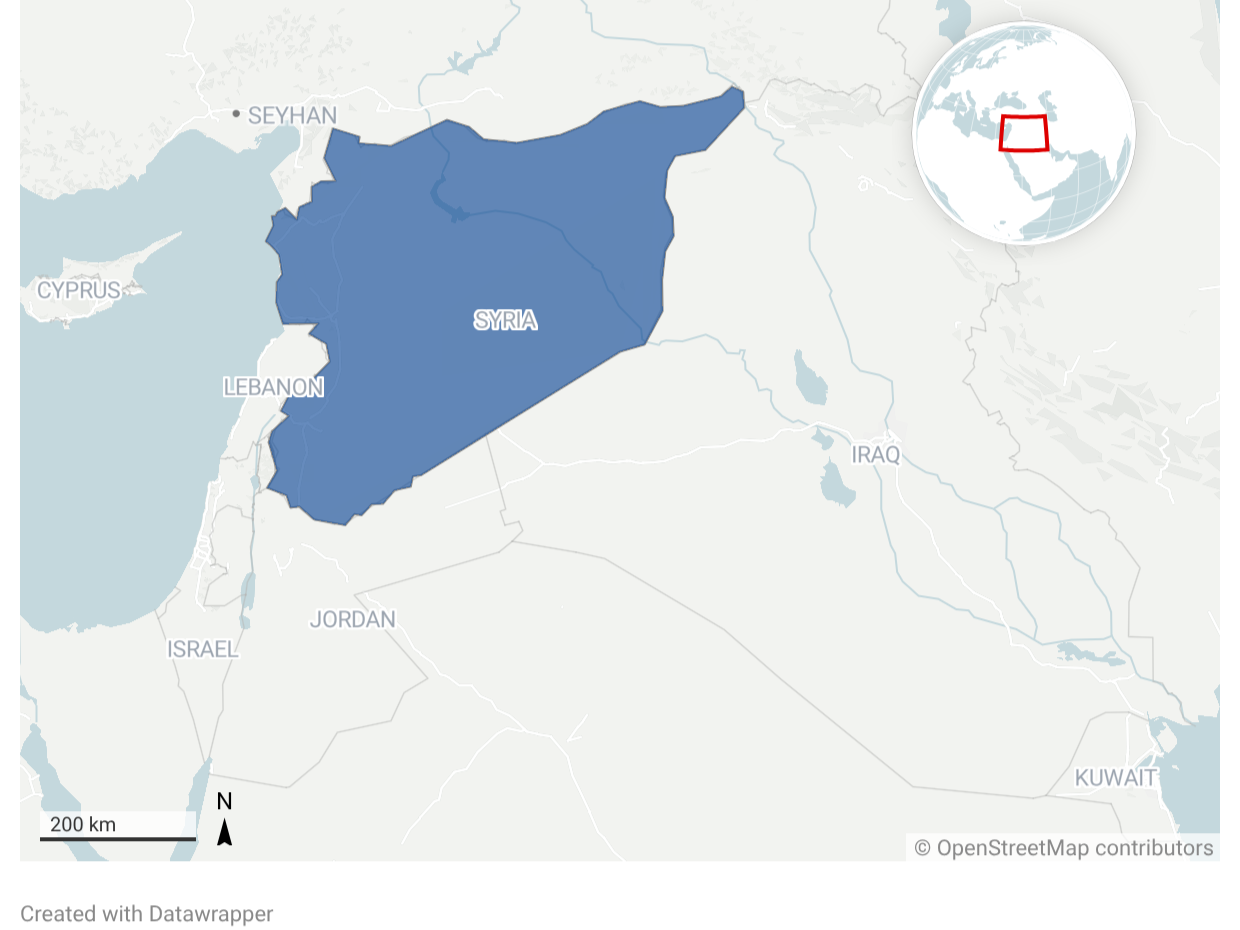

Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) Defeated in North-East Syria: Damascus Expands Power Over Fractured Country

By Neil Robertson | 27 January 2026

Summary

The new Syrian Armed Forces, along with tribal allies, have pushed the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) out of much of north-east Syria.

The latest offensive follows the breakdown of talks between the new Syrian government and the SDF, in which the inclusion of the Kurdish-dominated region in the new Syrian state was a key issue.

The SDF have surrendered in all but name, ceding to a 14-point plan by the Syrian government which would see the dissolution of their armed forces and near total inclusion into the Syrian state.

Context

On 6 January 2026 the Armed Forces of the new Syrian Government launched an offensive against Kurdish-led SDF in Aleppo, in northern Syria. The attack came in the wake of the breakdown of negotiations between the new Syria President Ahmed al-Shara’a and the SDF’s Mazloum Abdi over the nature of SDF ‘integration’ into the new Syrian state. While the new Syrian Government has uncompromisingly pushed for centralisation and the creation of a singular armed forces under a unified command, the SDF has been reluctant to cede any of the autonomy which they achieved during the height of the Syrian Civil War.

By 18 January, however, much of the SDF had been routed from north-east Syria by Damascus’ forces. The new Syrian government has reasserted control over long-held SDF territories, including Raqqa and Deir Ezzor, areas where Kurdish control had rested on fragile local alliances in predominantly Arab-majority districts. Furthermore, the government of al-Shara’a has taken control over vital oil fields in north-east Syria, further reducing the SDF’s room to manoeuvre before negotiations began.

Implications

The SDF has since ceded to a 14-point ceasefire agreement with the central government in Damascus. As part of the agreement the SDF has accepted the full administrative and military handover of Raqqa and Deir Ezzor, retaining control only over parts of Hasakah in the far north-east of the country. Furthermore, the SDF is to be effectively militarily disbanded, with former members allowed to join the new government forces on an individual basis only, rather than as units. Should the latter policy be implemented, the Kurdish revolution in north-east Syria will effectively be dead in the water – with Kurdish aspirations for autonomy supplanted by centralised Damascene rule.

The future of the SDF now appears to be incredibly uncertain, with two pathways open them. Firstly, they can accede to Government demands and fully integrate into the state, which will inevitably pave the way for their dissolution as a military/political force. Alternatively, the SDF may choose to dig in in their current positions and contest their territory militarily. In this scenario it is likely that they will attempt to increase the political and human costs for the government of al-Shara’a, and in doing so strengthen their hand in potential future negotiations.

Of major consequence to the stability of the region as a whole is the issue of ISIS prisoner camps in north-east Syria. As part of the 14-point agreement, the new Syrian government is to take full responsibility for the ‘ISIS file’ and the running of prisons housing former ISIS fighters. Reports indicate that during the fighting between the SDF and government forces that prisoners have escaped.

Kurdishstruggle/Flickr

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

Sporadic fighting is likely to continue as Syrian government forces consolidate their hold on previously SDF-held territory.

Increased ISIS sleeper cell attacks are highly likely as the temporary security vacuum allows the group to carry out attacks.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

The risk of heavy fighting is likely over key SDF-controlled cities in north-east Syria such as Kobani and Hasakah.

There is a realistic possibility that Syria will suffer from terrorist attacks carried out by ISIS detainees who have escaped prison during the fighting.

Long-term (>1 year)

There is a realistic possibility that elements of the SDF will transition into guerilla fighters, conducting an insurgency against security forces of the new Syrian government.

On the regional level, Israel has now lost its main proxy in Syria and a key balancing actor against aggressive Turkish expansionism in the region. Tensions between Turkey and Israel are likely to rise over the long-term.