Rising Hostilities Between Ethiopia and Eritrea Threaten to Unravel Stability Across the Horn of Africa

By Alex Blackburn | 31 October 2025

Summary

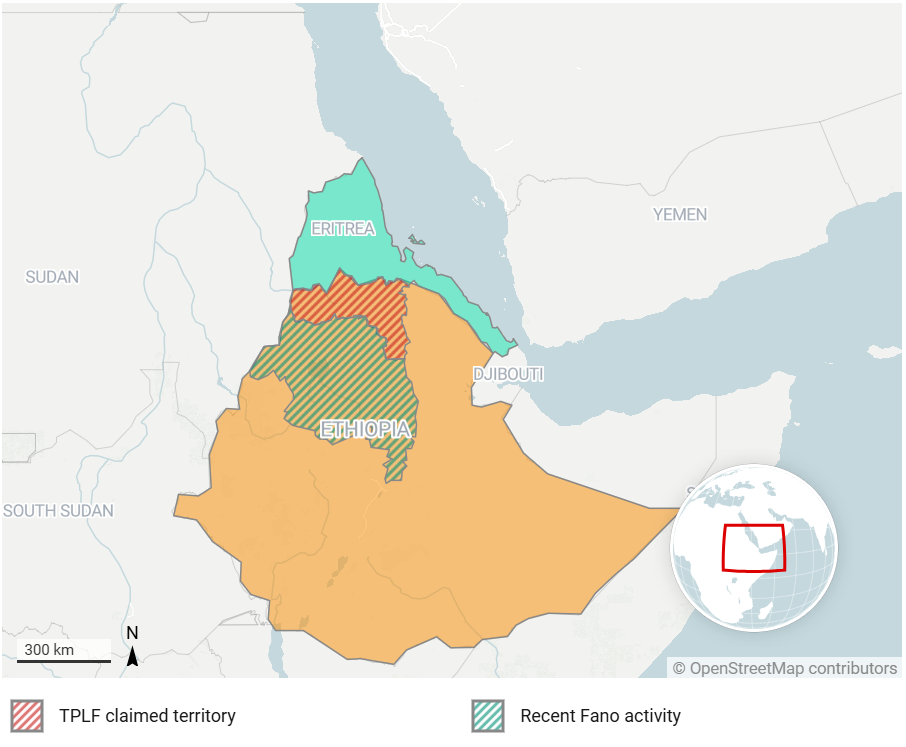

Ethiopia has accused Eritrea of colluding with the hardline Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) faction and arming Fano militias in Amhara, deepening a rift driven by Ethiopia’s renewed campaign to secure Red Sea access, a move Eritrea views as a direct existential threat.

The escalating hostility underscores a broader contest for influence in the Horn of Africa, where both nations’ actions threaten fragile stability, disrupt trade through the Red Sea corridor, and invite greater involvement from Gulf and global powers seeking to protect strategic maritime interests.

The conflict in Ethiopia’s Amhara region will likely intensify as Fano militias expand operations, potentially with quiet support from Eritrea and TPLF hardliners. This will stretch Ethiopia’s security forces, already fatigued from multiple internal conflicts.

Context

The fragile peace between Ethiopia and Eritrea is once again under severe strain, threatening to reignite one of Africa’s most entrenched rivalries. Ethiopia has formally accused Eritrea of colluding with a hardline faction of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) to prepare for war against Addis Ababa. In a letter sent to UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, Ethiopian Foreign Minister Gedion Timothewos alleged that Eritrea and TPLF elements are funding, mobilising, and directing armed groups operating within Ethiopia, most notably the Fano militias in the Amhara region.

These accusations come amid Ethiopia’s renewed effort to secure access to the Red Sea, which it lost when Eritrea gained independence in 1993. Since late 2023, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government has been increasingly vocal about the need for maritime access, describing it as essential to Ethiopia’s survival and economic growth. President Taye Atske Selassie went so far as to declare in parliament that the Red Sea and River Nile are “great water resources essential to Ethiopia’s existence.” Eritrea’s Information Minister, Yemane Gebremeskel, swiftly dismissed the rhetoric as “crass and pathetic,” accusing Addis Ababa of an “obsession” with maritime and regional power ambitions.

Simultaneously, Ethiopia faces an intensifying internal insurgency in its Amhara region. The Fano militia, once allied with Abiy during the Tigray War, has turned its guns on the federal government after rejecting a disarmament campaign. Claiming to defend the Amhara people from government repression, the group has expanded its agenda to seek the overthrow of Abiy’s administration. Ethiopian officials claim that Eritrea and the TPLF are backing the Fano rebellion, citing reports of coordinated operations, including a joint attempt to seize the strategic Amhara town of Woldiya in September.

Implications

The resurgence of hostility between Ethiopia and Eritrea carries profound implications for the Horn of Africa, one of the world’s most geopolitically sensitive regions. At its core, the tension reflects a collision between Ethiopia’s ambitions for regional resurgence and Eritrea’s determination to maintain its sovereignty and strategic buffer along the Red Sea coast.

For Ethiopia, access to the Red Sea is not merely symbolic but a strategic imperative. As one of Africa’s most populous countries and a significant regional power, Ethiopia’s dependence on Djibouti’s ports for nearly all its trade creates a sense of economic vulnerability and strategic frustration. The government’s growing assertiveness over the issue signals not only a desire for autonomy but also a recalibration of regional power dynamics. However, this assertiveness risks provoking Eritrea, which views any Ethiopian attempt to reclaim coastal access as an existential threat.

Eritrea’s alleged alliance with a TPLF faction and its support for anti-government militias such as the Fano mark a dangerous evolution in its foreign policy. Historically, Asmara has utilised proxy networks to project its influence while avoiding confrontation. If these allegations hold, Eritrea may be attempting to destabilise Ethiopia internally to prevent a military incursion or to secure leverage in future negotiations over trade and security arrangements. This escalation threatens to undo the fragile progress made in the post-conflict period. Both countries were key actors in the devastating 2020–2022 Tigray War, which killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions. The prospect of another round of warfare, whether through confrontation or proxy battles, could reignite regional instability that stretches from the Red Sea to the Great Lakes.

Broader Regional Significance

The stakes extend far beyond the Ethiopia–Eritrea border. The Horn of Africa sits astride the Red Sea corridor, a global maritime artery linking Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Instability here would directly affect international trade, energy supply routes, and security cooperation against piracy and terrorism.

Moreover, both Ethiopia and Eritrea are pivotal to the balance of power among external actors vying for influence in the Red Sea basin. Gulf states such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, as well as global powers like China and the United States, maintain vested interests in securing access and influence over regional ports and logistics hubs. Renewed Ethiopian–Eritrean hostilities could invite deeper foreign involvement, turning the Horn into a theatre of competing geopolitical interests rather than a zone of African-led stability.

Internally, Ethiopia’s instability risks spilling over into its borders. The country is already struggling with multiple internal insurgencies, ethnic violence, and economic strain. A weakened Ethiopia could embolden separatist movements or invite opportunistic manoeuvres from neighbouring states. For Eritrea, prolonged tension with Ethiopia risks deepening its isolation, worsening economic hardship, and fueling domestic discontent in a country already under heavy international sanctions and political repression.

Amod Photography/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

The conflict in Ethiopia’s Amhara region will likely intensify as Fano militias expand operations, potentially with quiet support from Eritrea and TPLF hardliners. This will stretch Ethiopia’s security forces, already fatigued from multiple internal conflicts.

Expect both sides to harden their rhetoric and increase border militarisation. Ethiopia is likely to frame Eritrea’s actions as external aggression to rally domestic unity, while Eritrea will portray Ethiopia’s Red Sea rhetoric as an expansionist provocation.

Skirmishes along the shared border or targeted cross-border raids cannot be ruled out, though both sides are likely to prefer deniable, low-intensity tactics.

Neighbouring states such as Djibouti and Sudan will likely maintain cautious neutrality, concerned about trade disruptions and refugee spillovers. However, the African Union and IGAD will struggle to mediate meaningfully, as both Ethiopia and Eritrea distrust multilateral interference.

Long-term (>1 year)

Without a negotiated maritime framework or confidence-building measures, the Ethiopia–Eritrea relationship has a realistic possibility of hardening into a long-term cold conflict. Ethiopia’s push for Red Sea access will remain central to its national strategy, driven by economic imperatives and population growth. Eritrea, perceiving this as an existential threat, will likely maintain a defensive, isolationist posture, turning the northern frontier into a militarised buffer zone reminiscent of the pre-2018 era.

A continued slide toward confrontation will likely threaten the Horn’s fragile security architecture. Trade routes through Djibouti and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait could face disruption, undermining global supply chains and energy transit.

At a political level, instability in Ethiopia, the Horn’s demographic and diplomatic anchor, has a realistic possibility of cascading into Somalia, Sudan, and South Sudan, unravelling regional cooperation efforts and undermining initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), further straining already struggling African economies.