New Gulf Investment Plan for Disarmed Hezbollah in Lebanon

By Trishnakhi Parashar | 3 November 2025

Summary

The United States (US) has initiated a regional investment plan, funded by Saudi Arabia and Qatar, to develop a southern Lebanese economic zone that would create jobs for Hezbollah members upon their disarmament.

The investment plan was proposed in August 2025 by senior US envoy Tom Barrack, following a review of the regional security landscape, with the aim of reducing Iran’s influence and simultaneously strengthening Gulf-US coordination.

Although this initiative could have been crucial for Lebanon’s growth, it faces constant challenges within the state from Hezbollah, making the full national disarmament target unlikely to be met.

Context

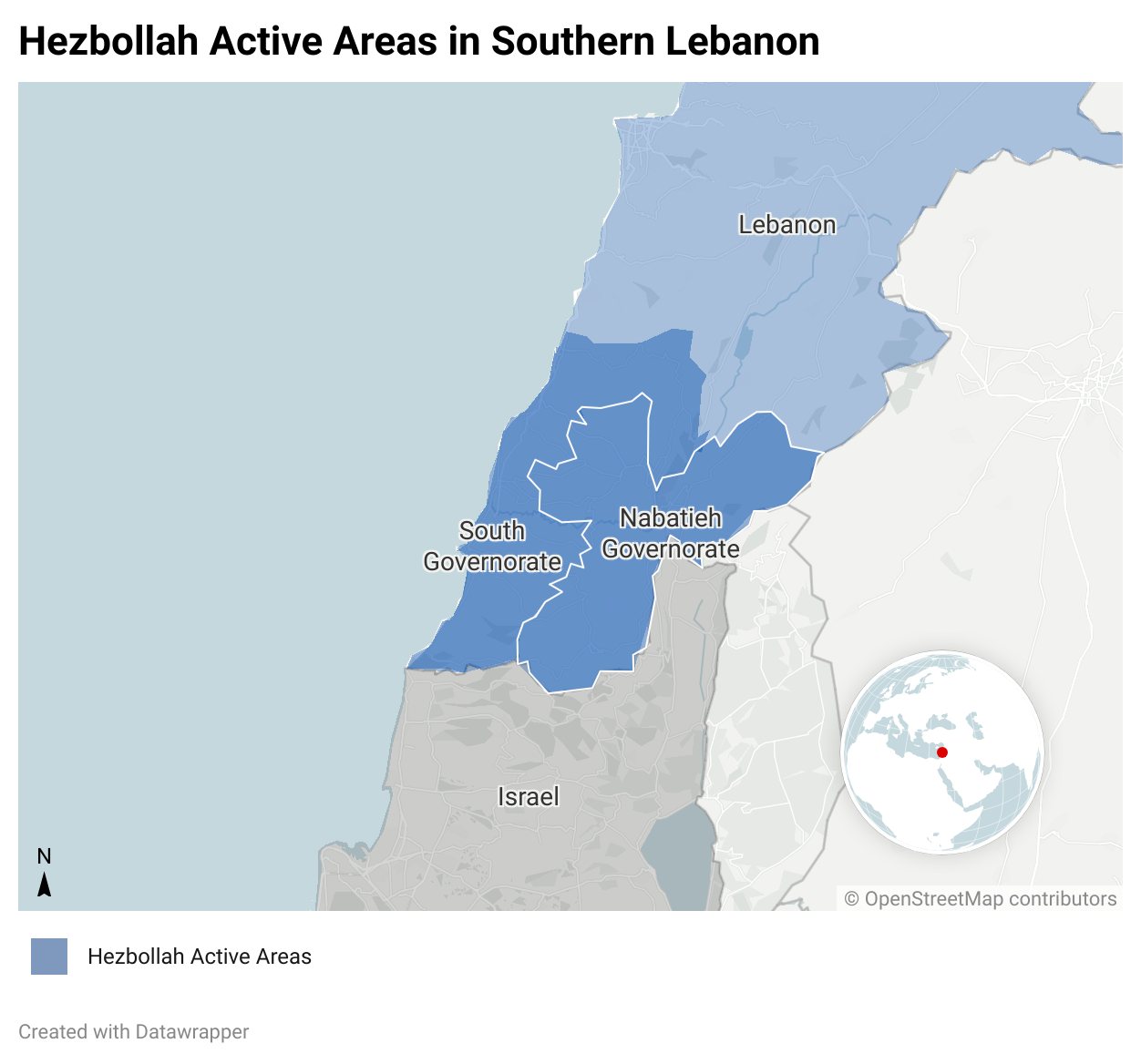

In August 2025, the Lebanese authorities, following a proposal by US Special Envoy Tom Barrack during his visit to the capital city, Beirut, announced a plan to disarm the Iran-backed Hezbollah group by the end of the year. The plan outlines an economic strategy for Lebanon that combines regional investment with security reforms. This plan also includes Saudi Arabia and Qatar to invest in an economic zone in southern Lebanon to create more employment opportunities for the former members of the Hezbollah group and its supporters who agree to lay down their weapons. Lebanon’s Prime Minister Nawaf Salam announced that the cabinet has approved the plan to keep all weapons under state authority.

Discussions between Israeli Strategic Affairs Minister Ron Dermer and Barrack led to the idea of establishing an economic zone in southern Lebanon during meetings held in August 2025 in Paris. The proposal involves establishing Lebanese state-owned factories in areas near the Israeli border. Reports also indicate that the US Administration is considering the name ‘Trump Economic Zone’ for this particular new economic area.

Israel and Hezbollah had a conflict starting on 8 October 2023 and intensified later on before a ceasefire was reached on 27 November 2024. The conflict had left over 4,000 dead and caused an approximate USD 11b in damage across southern and eastern Lebanon. Southern Lebanon holds strategic importance as it has been a centre of Israel–Hezbollah clashes and a key area of territorial dispute due to its proximity to the Israeli border.

The plan aims to facilitate capital inflow by primarily focusing on stabilising Lebanon’s deteriorating economy and advancing development projects. This plan is not a short-term relief package for Lebanon. It is designed as a sustainable path towards long-term stability for the region. It also seeks to attract Gulf investment while addressing regional security concerns. This proposal particularly targets groups that are currently funded by Tehran and are perceived to oppose Israel and Western influence. However, experts and residents have expressed scepticism that this plan will benefit Lebanese people, while Hezbollah leadership has consistently refused to give up its weapons. Therefore, these prevailing factors make it difficult to achieve the reforms. Moreover, uncertainty persists over whether full national disarmament will be completed on schedule.

Implications

The proposal indicates a coordinated effort to reassert influence in Lebanon through an incentive-based framework involving economic recovery and disarmament. If implemented as planned, it could potentially strengthen Lebanese domestic politics and reduce internal conflicts. However, Hezbollah and its allies may perceive the plan as an externally pressured initiative to weaken their political legitimacy and further risk of intensifying Lebanon’s socio-political polarisation. The walkout of Shia ministers from the cabinet debate shows a lack of national consensus. Continued resistance could lead to unrest if the Lebanese army uses force to disarm. Simultaneously, failure to do so may also put the investment at risk, and could maintain the current deadlock or further destabilise the situation.

Thereby, the conditioning of this investment plan on disarmament presents an operational risk. Risk because it ties financial assistance to a politically sensitive process. This interdependency creates uncertainty for both the Lebanese government and investors, making implementation and management more challenging.

The disarmament process aimed to reduce hostilities in the Israeli–Lebanese border area, limit the risk of new conflict and improve the security environment in southern Lebanon. According to media reports, Israel insisted that several villages on the border remain without residents to act as a buffer zone. Hezbollah’s leadership has stated that it will not disarm, saying Israel must withdraw from Lebanon and stop its attacks. Some observers support the plan as a step toward national sovereignty, while others remain uncertain if Hezbollah would agree to disarm without credible security assurances.

The involvement of primary investors, such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar, could provide critical financial support to Lebanon’s struggling economy. Moreover, the proposal to establish an economic zone in southern Lebanon could generate employment and encourage the reintegration of former Hezbollah members. The effectiveness of this investment depends on transparency, institutional reforms, and the prevention of political interference in the allocation of funds. Persistent corruption, coupled with fears and doubts about the plan’s objectivity, could erode investors’ confidence and delay benefits for the wider population.

Tasnim News Agency/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

The initial diplomatic coordination among Lebanon, the US, and Gulf states is highly likely to intensify, leading to more talks, detailed negotiations, creating pressure and monitoring.

Hezbollah is highly likely to resist handing over weapons, especially in strategic regions, such as southern Lebanon.

Israel is likely to continue conducting airstrikes, citing them as operations targeted only at Hezbollah infrastructures.

It is likely that no disarmament process or any notable change will occur in the short term.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

Partial implementation of the plan is likely to commence, such as the launch of preliminary infrastructure or employment projects in southern Lebanon.

Ministers' refusal to cooperate and Hezbollah’s unwillingness to disarm are likely to delay progress and decrease investor interest.

The Israeli military is highly likely to continue operations in Lebanon to remove any threat posed to Israel. Southern Lebanon may become more militarised.

Lebanon is likely to experience the worst economic situation, given Inflation, currency instability, and fiscal deficit problems. Investors are to avoid high-risk environments.

Long-term (>1 year)

There is a realistic possibility of partial or phased disarmament under strict conditions. But full or unconditional disarmament is very unlikely, given Hezbollah’s current posture, political support, and the security environment.

Hezbollah is likely to exert limited influence over security and decision-making. The political push could gradually shift alignment towards the Gulf and the West, likely to reduce Tehran’s influence.

The incomplete disarmament process is likely to exacerbate border tensions, resulting in a delayed or fragmented reform process.

If the Lebanese government succeeds in addressing the disarmament of Hezbollah prior to 2026 elections, as recommended by key foreign stakeholders, the improvement of the security conditions is likely to enhance economic growth prospects.

Hezbollah is highly likely to leverage civilian populations, particularly in southern Lebanon, when it perceives existential or political threats. Civilian mobilisation most likely takes the form of protests, demonstrations, or strikes, which might be framed as defending community interest or Lebanon’s sovereignty.