NATO’s 5% Target: Lessons from European Allies’ Path to 2%

By Francesco Pestrin | 25 November 2025

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the is publication are solely those of the author and do not reflect the positions, responsibilities, or policies of the author’s working affiliations.

Marek Studzinski/Unsplash

Summary

At the June 2025 meeting in The Hague, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) Allies committed to allocating 5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) annually to defence spending by 2035, raising ambition beyond the 2% target set in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Crimea.

Recent NATO estimates indicate all European Allies will reach 2% by 2025. However, distortions in spending, notably pension-related costs, have already constrained the effectiveness of this target in strengthening real military capabilities.

The focus on the consolidation of 2025 defence figures and current tight financial conditions will limit short-term upticks in funding. In the medium to long term, risks to inflating defence figures through the inclusion of non-strategic assets will hamper European military preparedness.

Context

Following the June 2025 NATO Summit in The Hague, Allies agreed to allocate 5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) annually to core defence spending by 2035. Of this, 3.5% will be earmarked under the official definition of NATO defence expenditures, which includes major equipment and personnel, while the remaining 1.5% will be directed to defence-related investments, such as civilian preparedness and defence industrial base. This represents an upward revision to the 2014 Wales Summit commitment of a minimum of 2% of Allies’ GDP to defence spending within a decade.

Recent NATO estimates for 2025 indicate that all European NATO members will meet the Wales target by year-end. The European Allies’ path to 2%, along with the current financial conditions, offers lessons to inform the move toward 5%.

Implications

The road to 2%: Spending delays and accounting distortions

Translating political momentum into sustained increases in defence spending has proven difficult so far. Since 2014, NATO’s European Allies have taken an average of 9 years to meet their 2% commitment, with some countries that reached it early on but failed to maintain it consistently until recently. The delay in reaching 2% is partly explained by diverging European views on a new Russia policy after 2014, with governments differing in their perceived vulnerability to competing security threats.

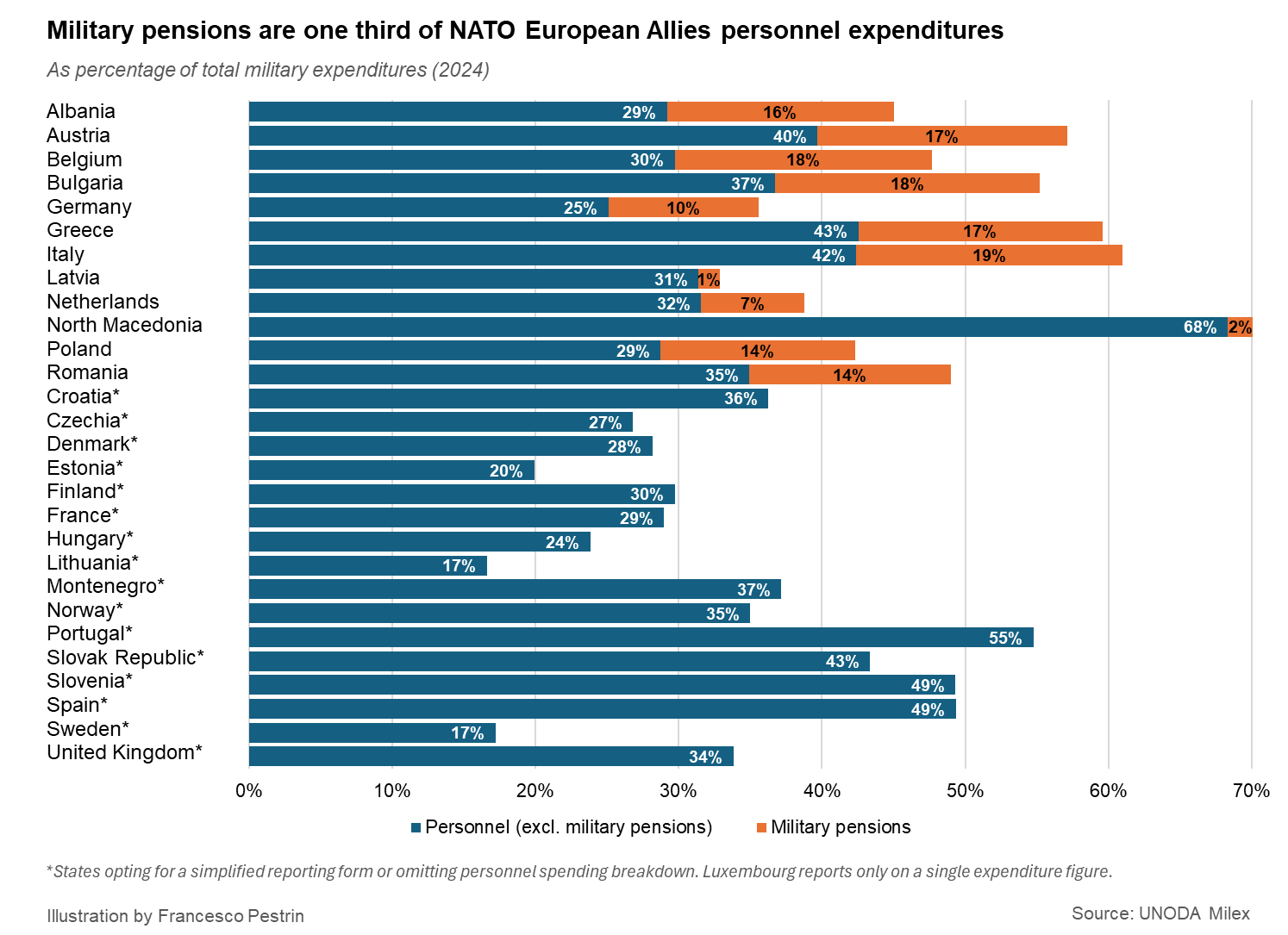

Spending distortions still need to be addressed. Personnel expenditures, which represent on average 40% of European Allies’ total military spending, are often used as an accounting tool to strategically inflate defence figures. Among 12 NATO European Allies reporting on pension-related costs, nine indicate that at least one-third of their personnel funding goes to military personnel no longer on active duty. Estimates suggest that France would lose 0.3 percentage points of its 2% figure due to pension spending.

Limited fiscal space and uncertain growth dividends will constrain further spending

Current financing conditions leave little room for defence budget upticks without higher tax revenues. Past military build-ups were mainly financed through a mix of borrowing and tax increases, these aimed at managing the additional debt load over the medium term. Elevated debt levels in Europe, such as those contributing to France’s recent credit downgrades, are driving up borrowing costs, limiting fiscal space. States cannot durably rely on debt-financed military spending effects on growth to ensure the sustainability of public finances either. Fiscal multipliers, i.e., the increase in national income for each pound of government spending, are typically estimated in the 0.5-0.8 range. These are found to be zero (or even negative) for countries with a debt-to-GDP ratio above 60%, which is now the case for half of NATO European Allies.

Defence innovation could support potential output, but only if private R&D is upscaled. While European Allies have formally met the 2% target through higher relative spending on equipment, operations and maintenance, and R&D, the latter has suffered from chronic underfunding with respect to the United States (US). In the euro area, defence procurement largely targets existing weapons systems, with advanced electronics still accounting for only a small share in 2022.

Even if resources were available, Europe’s defence industry faces absorption constraints. Without European-scale consolidations of national defence actors and quicker technological diffusion, an increase in spending would result in procurement inefficiencies and allocation to projects with limited operational or strategic value.

The 5% defence spending target sends a decisive signal to NATO adversaries about the commitment of European Allies. To serve as an effective deterrent, coordinated investment efforts are essential, driven at the EU level (ReArm Europe plan) and supported by the EU’s external action framework. Yet, modernising and repurposing industrial capacity to meet excess demand will require time, weighing on operational readiness. Opposition from local constituencies could bolster extremist parties; it is crucial to frame these spending increases as a necessary response to the end of the “peace dividend” era, financed primarily through higher public debt rather than reallocating funds from other budget areas.

European states with stronger fiscal positions and lower debt-to-GDP ratios are likely to reap greater economic benefits from these defence investments. NATO and EU ties will however ensure that these relative advantages will work at the benefit of all member states, reinforcing unity against common security threats.

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

Consolidation of 2025 defence spending estimates is highly likely, with a state focus on confirming attainment of the 2% target. Draft budgets for 2026 are expected to include a larger defence allocation, leveraging the current political momentum.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

The 1.5% component of the 5% target will grant states flexibility in managing defence resources, but this at the likely risk of tagging non-strategic assets as defence-related. Distortions in defence accounting will likely continue to mask actual military capabilities.

Long-term (>1 year)

The objective to attain the target in 10 years’ time will unlikely provide incentives to meaningfully increase spending across European Allies, at least not until the revision of the expenditure trajectory expected for 2029.

Medium chance of losing political momentum if ceasefire in the Russo-Ukrainian War is achieved and endures.

States distant from Russia are likely to sustain defence spending if a clear business case exists for state-owned or partially state-owned enterprises, for example through economies of scale at the European level.