Israel’s Recognition of Somaliland: Implications for African Sovereignty and the Reconfiguration of Regional Balances

By Hossamaldeen Ibrahim | 17 February 2026

Summary

Israel’s formal recognition of the Republic of Somaliland on 26 December 2025 marks a momentous shift in Horn of Africa geopolitics, introducing a new external actor into longstanding territorial disputes and strategic contests in the region.

This recognition diverges from the long-standing international norm of territorial integrity of Somalia and is widely condemned by the African Union, the Arab League, and neighbouring states as a violation of international law and a dangerous precedent in a fragile security environment.

This diplomatic shift adds a new layer to competing interests in a fragile region marked by overlapping conflicts, security concerns in Yemen and the Red Sea, and competing external influences including the Gulf states, Turkey, and global powers.

Context

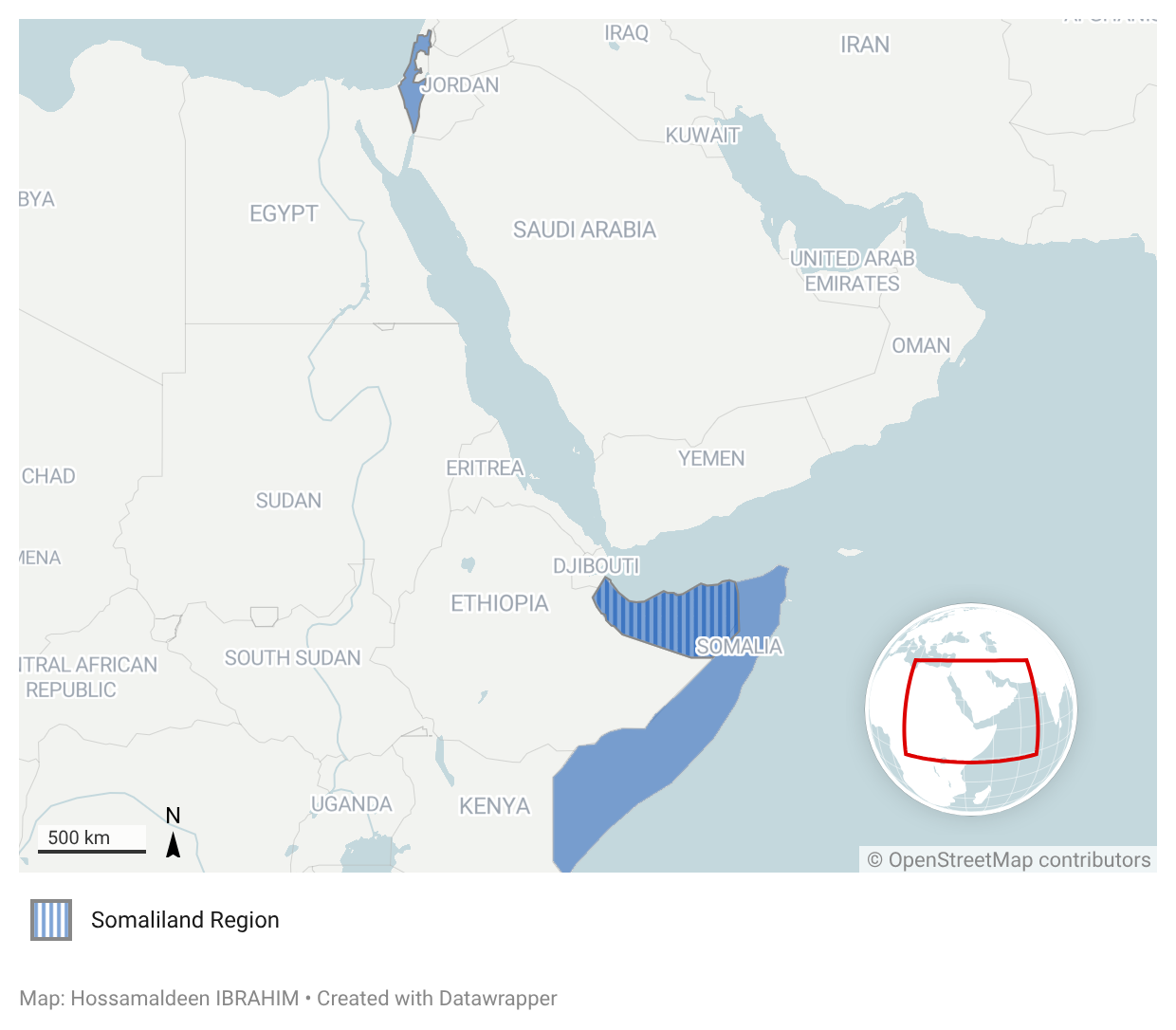

Somaliland is located in the northwest part of Somalia. Briefly independent in 1960 before uniting with Italian Somaliland to form the Somali Republic, Somaliland later declared unilateral independence amid civil war in 1991. Despite maintaining relative internal stability compared to the rest of Somalia, it has not been widely recognised internationally as a sovereign state. as opposed by Somalia’s federal government backed by the African Union and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.

On 26 December 2025, Israel became the first United Nations member state to formally recognise Somaliland’s independence. Israeli officials indicate that the decision reflects longstanding strategic priorities: securing maritime and intelligence advantages along the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden , particularly in light of regional maritime insecurity and attacks on shipping routes.

Implications

Israel’s recognition of Somaliland carries strategic, political, and geoeconomic consequences that extend beyond bilateral diplomacy and into the wider Red Sea-Horn of Africa security architecture.

Somaliland’s coastline along the Gulf of Aden, situated immediately south of the Bab al-Mandab Strait , a maritime chokepoint through which approximately 12-15% of annual global trade transits. Recognition creates a realistic pathway for enhanced security cooperation, potentially including maritime surveillance, signals intelligence coordination, and counter-threat monitoring linked to militant activity emanating from Yemen. Since 2023, Houthi forces have targeted commercial and Israeli-linked shipping in the Red Sea, underscoring the operational relevance of expanded monitoring capabilities in adjacent waters.

Such cooperation could strengthen tactical responses to maritime threats and expand Israeli strategic depth vis-à-vis Iran-aligned networks operating in Yemen and the Gulf of Aden. However, the securitisation of Somaliland also introduces escalation risks. The emergence of a new security axis in the Red Sea basin is likely to attract counterbalancing behaviour from opposing actors, increasing the probability that Somaliland becomes a theatre for indirect competition rather than a stabilising node.

Regional reactions reflect diverging strategic calculations. Turkey, which has deepened defence and security cooperation with Somalia, is likely to interpret the recognition as undermining its own regional posture. Egypt and members of the Arab League have framed the development as a breach of international norms, linking it to broader concerns over Red Sea security equilibrium. Ethiopia, which briefly pursued sea access arrangements via Somaliland in 2024, is likely to adopt a cautious position, balancing its maritime ambitions with the risk of further destabilising relations with Mogadishu. These dynamics deepen competitive layering in the Red Sea basin and increasingly mirror broader Middle Eastern rivalries.

Politically, the recognition challenges the long standing continental norm of preserving inherited borders, a principle that has functioned as a stabilising mechanism across Africa. Condemnation from regional organisations reflects concern over precedent setting implications for other separatist movements. Within Somalia, the development is likely to intensify internal political tensions, particularly the separatist movement in Puntland. This environment presents a realistic possibility of extremist groups, particularly al-Shabaab, exploiting sovereignty narratives to mobilise support or justify intensified operations. As a result, ongoing state-building and institutional stabilisation efforts may face renewed strain.

The economic dimension is similarly intertwined with security and geopolitics. Berbera port has already emerged as a significant logistics node, supported by Emirati investment and integration into regional trade corridors. Increased international engagement could expand foreign direct investment and enhance trade connectivity. However, absent broad international recognition, legal and financial constraints will continue to limit full integration into global markets. Moreover, geopolitical competition risks distorting infrastructure development, prioritising strategic positioning over economic efficiency and regional coherence.

Maritime insecurity and shifting alliance structures have wider systemic implications. Disruptions in Red Sea shipping reverberate through Suez Canal revenues, global supply chains, and energy markets, elevating the geoeconomic significance of developments in Somaliland beyond the immediate region.

Across the Horn of Africa, the move compounds existing fault lines. It complicates Ethiopia-Somalia relations, may challenge Djibouti’s established role as a primary regional maritime hub, and increases the likelihood that external powers deepen asymmetric military or economic engagement to safeguard strategic interests. The cumulative effect is not immediate systemic rupture, but rather a gradual intensification of competitive geopolitics anchored in ports, maritime corridors, and contested sovereignty narratives.

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

Diplomatic contestation is highly likely, with Somalia pursuing legal and multilateral challenges. Security rhetoric around Somaliland’s ports will likely intensify, alongside increased intelligence coordination. Regional actors are expected to recalibrate alignments in response to shifting Red Sea dynamics.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

Maritime security competition in the Gulf of Aden is likely to evolve amid instability linked to Yemen. Political fractures within Somalia may deepen, creating a realistic possibility of heightened extremist activity. External powers are likely to expand engagement across Red Sea trade corridors.

Long-term (>1 year)

A partially reconfigured Red Sea security architecture is a realistic possibility. Debate over territorial integrity and recognition norms is likely to persist. Structural geopolitical shifts in the Horn of Africa may intensify wider power competition.