Hydropolitics of China

Divya Narvekar | 27 May 2025

Summary

The Brahmaputra—called the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet originates in China, flows through India, and ends in Bangladesh. This makes it a classic case of transboundary water politics, with China as the upper riparian, and India and Bangladesh as downstream stakeholders.

Transboundary watercourses present a challenge in terms of water management as they pass through different territories with varying national interests, resulting in water conflict among the riparian countries.

Lack of hydrological data sharing, especially from China, limits early warning systems and disaster preparedness.

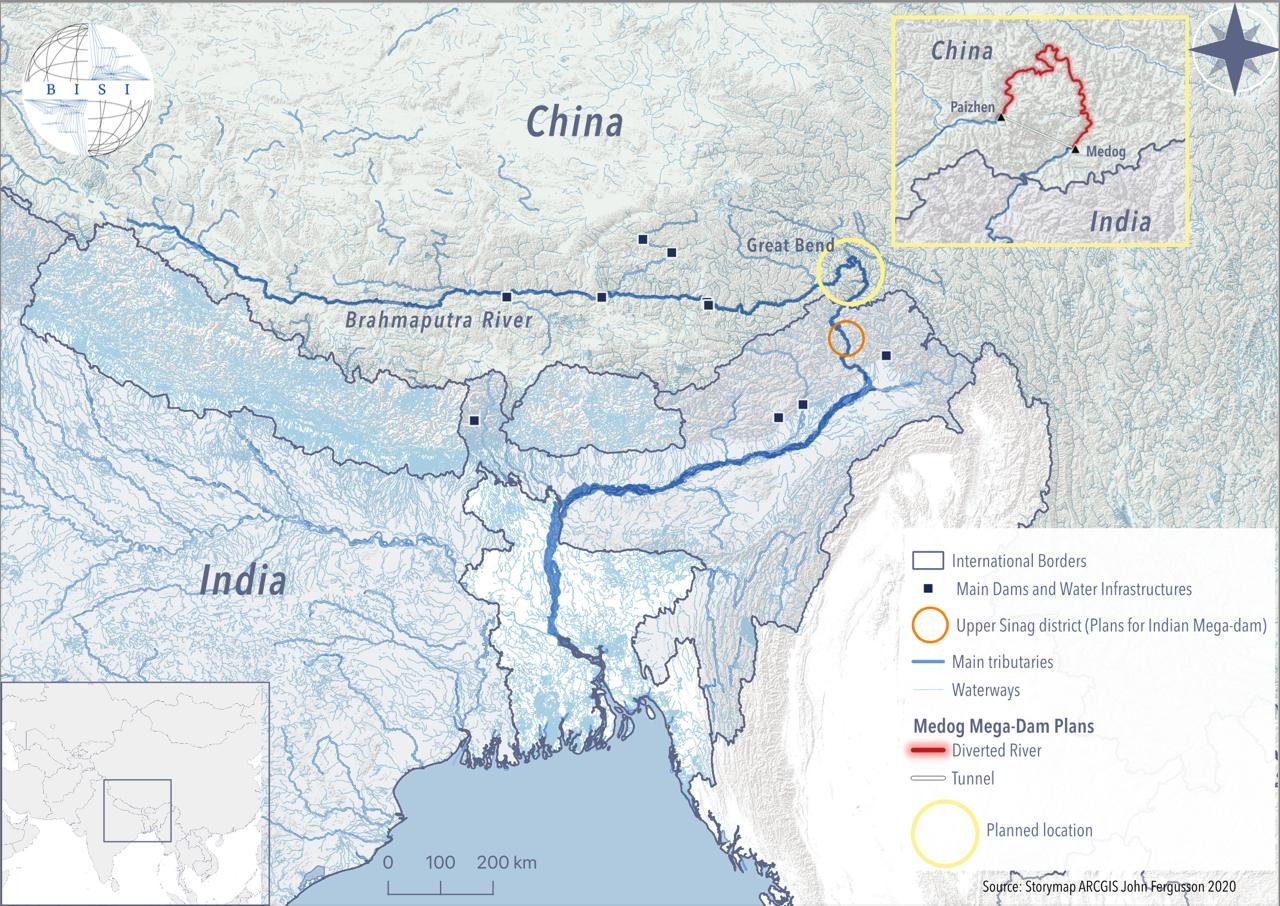

In recent times, China has emerged as the most prominent dam-constructing state. The Brahmaputra River, originating in the Kailas range of the Himalayas, flows 2,300 miles through China, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Myanmar. while collectively it is regarded as the Yarlung Zangbo Brahmaputra-Jamuna River System. On 25 December 2024, China approved the construction of the world’s largest hydropower project, Medog Hydropower Station, raising several concerns and strong reactions, especially from downstream nations such as India and Bangladesh.

China is building the proposed dam close to the Great Bend, where the river curves into India. The location for the dam is a seismically active and ecologically fragile region. If completed, it could become one of the world’s largest dams while posing a serious hydrological threat, especially in transboundary river systems and ecologically sensitive zones. These threats arise from their scale, upstream location, and capacity to control or alter river flows, which can affect millions of people downstream. The proposed Great Bend Dam aims to divert the main flow of the Brahmaputra River near Motuo, situated at an elevation of around 2,800 meters. Using a tunnel, the water would be rerouted to emerge near Medog, effectively bypassing the river's natural U-shaped turn known as the Great Bend. The dam will be capable of producing 60 to 70 gigawatts of electricity—more than thrice the output of the Three Gorges Dam, which currently holds the title of the world’s most powerful hydroelectric facility. China uses its water resources, especially rivers that originate in its territory, as a tool of domestic development and international diplomacy. Given China’s upstream geographic position on many major transboundary rivers in Asia, its water management decisions have far-reaching implications for neighbouring countries.

The Brahmaputra is often discussed as a location of future water conflicts between China and India. The multipurpose dam, which will be built on the Indian side of the disputed India-China border, is expected to inundate 11,624 acres of forest land and threaten wildlife. The issue becomes increasingly critical in light of the rising water scarcity in both countries, the growing demand for water across all sectors, and the lack of water sharing agreements. China's actions upstream are shaping the hydropolitical narrative in South Asia. Without legal frameworks and cooperative management, the river may evolve from a shared resource into a source of contention, especially as water becomes an increasingly securitised issue. The construction and operation of the dam could disrupt local ecosystems, affecting biodiversity, sediment transport, and fish migration. China’s upstream control over the river and its extensive dam-building projects have raised concerns in downstream India and Bangladesh about potential impacts on water availability, agriculture, and livelihoods. The river system is critical for the socioeconomic well-being of millions of people, yet the competing demands for water resources have led to geopolitical tensions.

China’s lack of transparency in sharing data on water flow and dam operations could severely affect India’s and Bangladesh’s water security. China’s extensive dam building in recent years aims to harness hydroelectricity to power remote and underdeveloped regions like Tibet, while reducing its dependency on coal for a green energy transition.

The hydropolitics of the Brahmaputra River presents multifaceted implications, particularly in the context of rising water scarcity and increasing demand in the region. Politically, the absence of a binding water-sharing agreement between India and China—two regional powers with a history of strategic rivalry—creates an atmosphere of mistrust and competition. Unpredictability in river flows disrupts agricultural cycles, water storage planning, and hydroelectric projects, complicating resource management and exacerbating interstate tensions within India and between India and Bangladesh. To date, China has built 11 dams on the Lancang River, and 11 mainstream dams in the lower Mekong and 120 dams in the tributaries are under construction or are being planned. From a security standpoint, water infrastructure along contested border regions, particularly in Arunachal Pradesh and Tibet, may be perceived as strategic assets or threats, making water a potential flashpoint in broader geopolitical conflicts. Additionally, the potential for water manipulation, such as withholding or releasing flows, adds a coercive dimension to regional relations.

Сайга/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

Excess water release from upstream (intentional or due to heavy rainfall) will highly likely lead to floods in Assam and northern Bangladesh.

Loss of crops and livestock due to flooding or irrigation failure is likely throughout the rain season.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

The site of the development is located along an earthquake-prone tectonic plate boundary. Such extensive construction in the valley will likely increase the frequency of earthquakes, landslides or catastrophic flooding.

There is a high likelihood of eco-migration or population displacement due to land degradation and declining agricultural viability.

Lack of hydrological data sharing, especially from China, limits early warning systems and disaster preparedness.

Long-term (>1 year)

There is a possibility that Chinese dams and climate change may reduce downstream flows, impacting agriculture and drinking water in India and Bangladesh.

Through extensive dam building and water diversion projects, there is a realistic possibility of increased salinity, silting, and changes in flood and drought cycles in downstream regions. Such disruptions would have profound effects on agriculture, fishing, and the livelihoods of millions in India’s northeastern states.