After Ukrainian Strikes: What Is Kazakhstan’s Future with the CPC?

By Erlan Benedis-Grab | 28 January 2026

Summary

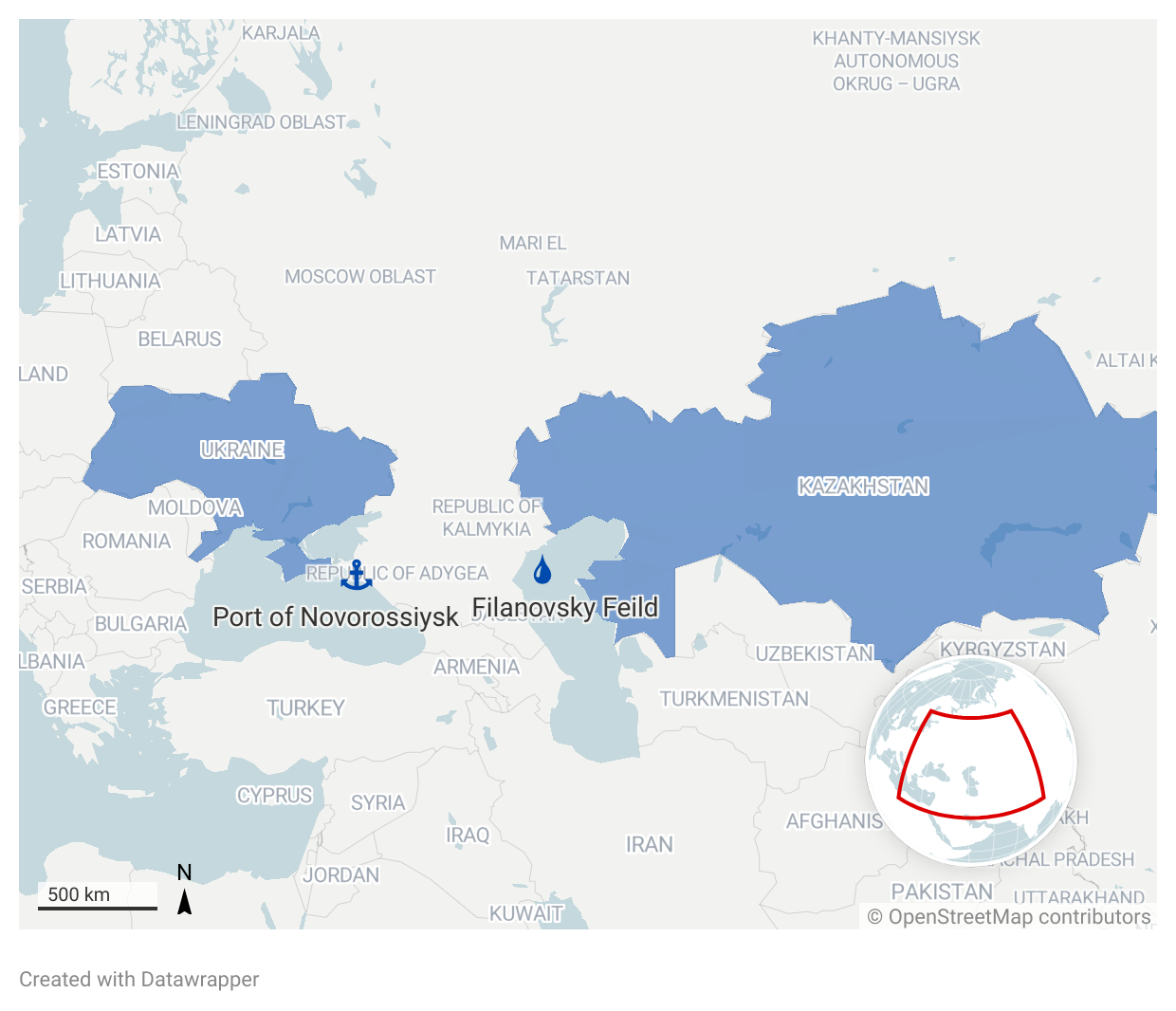

On 29 November 2025, a Ukrainian naval drone hit a Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) processing terminal near Novorossiysk, seriously impacting operations for Kazakh exports.

Following this, in December 2025, Ukraine carried out multiple strikes on Lukoil’s Filanovsky and Korchagin offshore facilities in the Caspian Sea, hitting multiple sites and disrupting oil and gas production.

Kazakhstan has responded by temporarily reducing its exports to Russia from the Kashagan oil field, which is along the CPC Route and increasing exports to alternate destinations.

Kazakhstan has repudiated Ukraine’s actions as destabilising.

Context

The Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) is a 1,500 km pipeline that carries oil from Kazakhstan’s fields westward through southern Russia. Launched in 1992 and completed in 2003 for USD 2.6b, it remains a rare example of major investment projects on Russian territory with substantial Western participation.

On 29 November 2025, Ukrainian naval drones struck the area of Novorossiysk for a third time in November 2025, targeting the CPC’s single-point moorings (SPMs) structures. SPMs are offshore loading buoys that allow tankers to take on crude directly from a pipeline without docking at a conventional port. This was followed by another attack against oil-pumping infrastructure and on Novorossiysk’s loading stands & manifolds. As a result, only SPM-1 remained operational, sharply constraining loadings for weeks and creating a bottleneck that persisted into early 2026.

In mid-December 2025, Ukraine carried out its first reported strikes in the Caspian Sea, targeting Lukoil’s Filanovsky and Korchagin offshore platforms. On 13 January 2026, Ukraine again targeted CPC-linked activity, reportedly striking at least two tankers en route to Novorossiysk.

The attacks triggered a diplomatic dispute. Kazakhstan condemned them as “an action harming the bilateral relations of the Republic of Kazakhstan and Ukraine”.Ukraine rejected claims that its actions were directed at Kazakhstan or other third parties. In January, Astana reiterated its protests and appealed to the U.S. and Europe to support security for the CPC. Kazakh MP Aidos Sarym warned that “such actions create serious risks not only for Kazakhstan, but for countries that depend on these energy supplies,” adding that Western partners should press Kyiv to “choose its goals”

Implications

The CPC accounts for 80% of Kazakhstan’s crude oil exports and thus has a significant share of export revenue, making it critical to Kazakhstan’s exports. In December, Energy Minister Erlan Akkenzhenov said cumulative production losses reached about 480,000 tons—equivalent to more than a tenth of Kazakhstan’s daily output in rate terms.

As such, in December, Kazakhstan redirected 300,000 tons of crude from the CPC via the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, Atasu–Alashankou pipeline (to China) and Atyrau–Samara pipeline (to Russia). Unfortunately, this is a stopgap. Kazakhstan cannot reduce outflows via the CPC long-term, as there are no viable alternatives. Neither of the other pipelines has the capacity to meet the export demands of oil. Still, Astana is trying to expand capacity at the margin —working with the EBRD to modernise Aktau port logistics and targeting an increase in BTC-route exports to about 1.6 million tons in 2026.

At the same time, oil underwrites the Kazakh state. With few CPC-scale alternatives, any sustained squeeze on export volumes threatens the budget and the elite interests tied to oil rents, making diversification politically costly. If revenues fall, the pressure can trigger tenge volatility and inflationary pressures that fuel social discontent.

These strikes sit in a legal grey zone. International humanitarian law restricts attacks on civilian objects, but both Ukraine and Russia have targeted energy assets by arguing they serve dual-use functions that support the war effort. Russia’s sustained strikes on Ukraine’s energy system also undercut Moscow’s credibility when it calls for restraint, making its objections appear inconsistent.

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 3 months)

It is likely that CPC flows recover, but bottlenecks persist under the threat of strikes.

It is likely that rerouting continues but stays marginal in volume. Kazakhstan will keep leaning on “pressure-relief” routes (Atasu–Alashankou/China and BTC), but these will not replace the CPC in scale.

Diplomatic friction is likely to continue between Kazakhstan and Ukraine. Astana condemns the strikes and urges Kyiv to stop hitting CPC-linked infrastructure, while Ukraine insists it isn’t targeting Kazakhstan.

Medium-term (3-12 months)

Diversification at the margin is likely to become routine. It is likely that the regular use of Atasu–Alashankou and BTC routes will increase.

Long-term (>1 year)

A sustained shift away from CPC is unlikely because alternatives can’t absorb CPC-scale volumes and there is marginal elite incentive to fund the costly infrastructure expansion needed to change that.