Icebreakers of Influence: NATO and the Dual-Use China-Russia Arctic Threat

By Larissa Alves Lozano | 2 February 2026

Summary

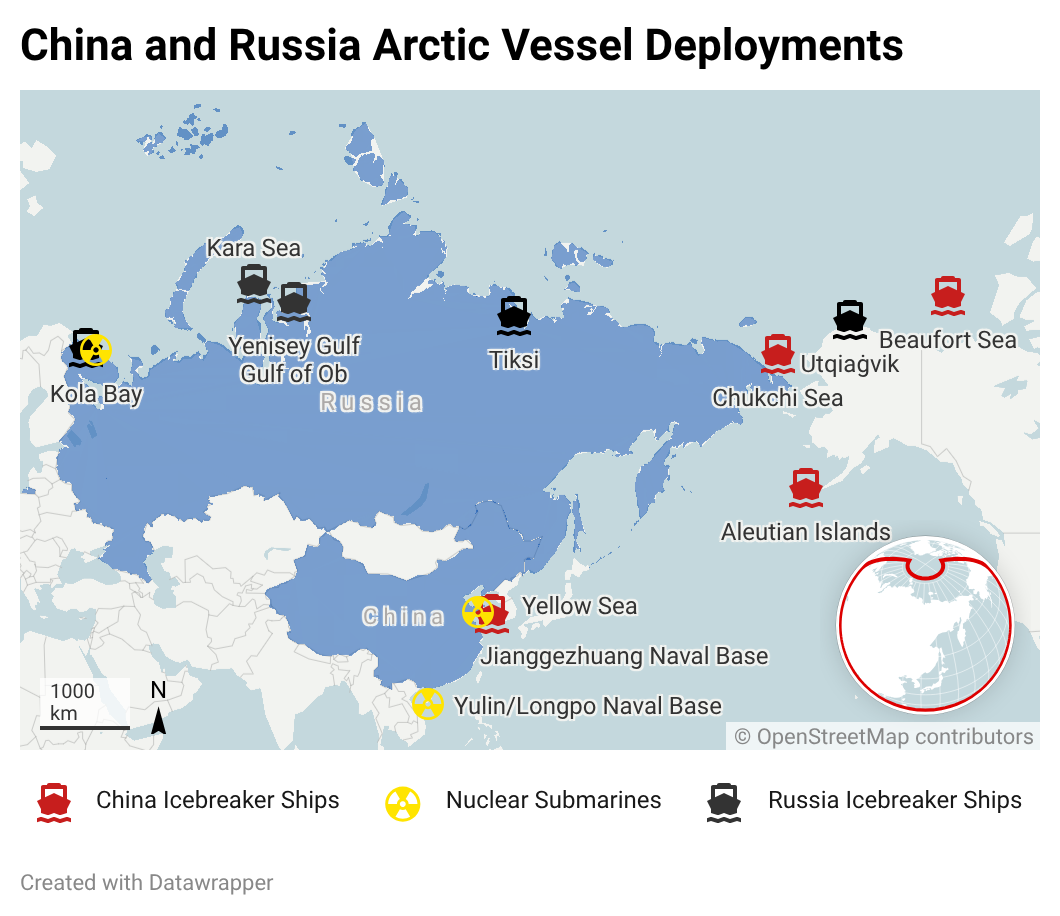

China has cemented its place near NATO’s northern flank by claiming “Near-Arctic” status and partnering with Russia in developing icebreaker ships.

In addition to natural resource and trade objectives, China and Russia’s development of modern icebreakers, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and nuclear submarines showcase dual-use agendas.

The growing China-Russia “two-peer challenge” has placed NATO’s ageing icebreaker and nuclear submarine arsenals on high alert, compounding existing resource competition, regional sovereignty, and nuclear deterrence challenges with the added risk of asymmetrical and anti-submarine conflicts.

China and Russia: The Two-Peer NATO Threat

During the 56th World Economic Forum annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte expressed security concerns about Russia and China’s increased partnership in the Arctic region, illustrating a 2022 joint statement emphasising that “friendship between the two States has no limits.” NATO now faces a growing “two-peer challenge” in its northernmost territory, spanning natural resources extraction and extensive research and intelligence gathering.

Since 1996, the Arctic territory has been jointly administered under international law by the Arctic Council states: the United States, Canada, the Kingdom of Denmark (includes Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Russian Federation. In 2013, the Arctic Council gained a new permanent Observer: China. These concerns are exacerbated by its close partnership with Russia through joint military exercises and intelligence sharing. Russia has clear nuclear deterrence and military interests in the region, and its fleet currently sits at 30+ submarines, 30+ surface warships, and about 57 icebreaker ships. Russia is also developing a nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed underwater drone called Poseidon, which was tested in late 2025.

Tensions heightened in 2018, when China declared itself a “near-Arctic State” and has deployed various icebreaker vessels off the coast of Alaska and along the Pacific Ocean. Its fleet of icebreaker ships is rapidly growing: Xue Long 2, Shen Hai Yi Hao, Ji Di, Haibing, Zhong Shan Da Xue Ji Di, and Tan Suo San Hao, its newest icebreaker. Of those, two are equipped with remotely-operated and autonomous/unmanned underwater vehicles (AUVs or UUVs). Additionally, China is developing the world’s first AI-powered extra-extra-large long-range underwater drones (XXLUUVs), which can be up to 42 meters (130 feet) in size.

Dual-Use Arctic Vessels: NATO’s New Challenge

The Arctic is key to China’s global influence. In establishing the Polar Silk Road along the Northern Sea Route, its position in the Arctic Council, and maritime innovations are all evidence that China seeks to control another major maritime chokepoint crucial for both trade and military maritime transit. Additionally, the increase in icebreakers equipped with AUVs and submarine deployments further exposed China’s two-sided agenda. In fact, China has overtaken Russia as the world’s second-largest nuclear submarine operator. Regardless of peaceful scientific data gathering and trade ship traffic, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) activities are inherently dual-use, primarily for China’s extensive record as a surveillance state and its interconnected civilian and military ISR means. In fact, warnings of dual-use research have been raised by the U.S. Congress on the China-Iceland Arctic Observatory, thus the seven NATO Arctic states should remain vigilant of PRC-sponsored ISR in the region and its wider global influence campaign.

With the PRC’s increased regional leverage and partnership with Russia, there are now two non-NATO countries in a NATO-dominated strategic territory with advanced icebreakers and underwater drone capabilities that rival all of NATO’s maritime arsenal combined. As of 2025, NATO members possess about 45 icebreakers combined, which is fewer than Russia and China combined, and about 65% of them are past their design life, ranging from 30 to 55 years old. This “Icebreaker Gap” poses significant strategic disadvantages for NATO in monitoring and countering buildups from Russia and China. Despite recent efforts such as the 2024 Icebreaker Collaboration Effort (ICE Pact), the recent U.S.-Finland icebreaker deal, and AUV prototype testing in Germany and the United States, NATO has a long way to go to match Russia and China’s capabilities. This gap widens now that underwater drones have come into play, posing new challenges for existing surveillance capabilities. Furthermore, Russia and China’s advancing underwater monitoring capabilities could pose a risk for underwater data and internet cables that transmit information between NATO countries.

The full extent of China and Russia’s partnership in the Arctic remains to be seen, as large-scale underwater drones are still in the development phase. However, NATO’s increased defence spending and icebreaker fleet modernisation point to a new era of Arctic strategy focused on countering unmanned systems and dual-use ISR from China and Russia. NATO’s Arctic posture will only succeed if the “Arctic Seven” work in unison by leveraging their unique regional strengths, partnering with regional allies such as South Korea, and maintaining satellite and underwater intelligence cooperation, mimicking the Russia-China alignment.

Forecast

Short-term (Now - 12 months)

It is unlikely that NATO will close the Icebreaker and AUV gaps at a pace to rival Russia and China if it continues extending its fleet design life rather than investing in new manufacturing sites and building new vessels.

China and Russia are highly likely to continue expanding their underwater drone infrastructure, especially in response to NATO’s fleet modernisation efforts and goals to increase joint patrols in the region.

Long-term (>1 year)

As global presence in the Arctic increases and NATO-Russia-China tensions continue to rise, it is also likely that the threat of asymmetrical warfare between vessels will remain prominent and must be a permanent component of Arctic security strategies.

Private defence manufacturers in the United States and Europe will almost certainly play a crucial role in achieving AUV and icebreaker fleet objectives to help balance budget overruns and timeline delays from government-funded projects.